A Mirror for the Masked Autistic

autie-biography, autistic self-help, and the dream of your shame

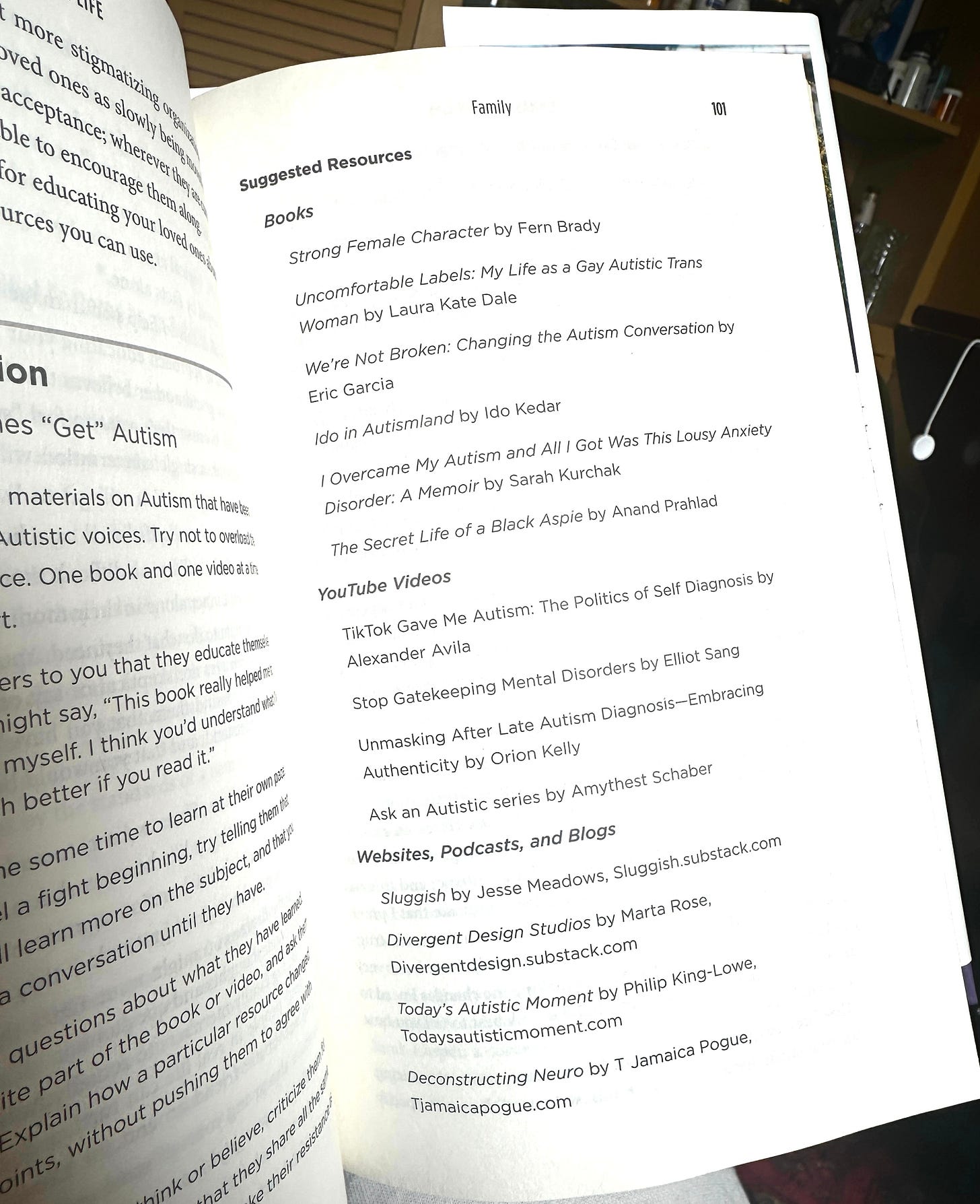

Sluggish is included in a list of resources in my friend Devon Price’s new book, Unmasking for Life, alongside a bunch of people whose work I really dig and admire!

Unmasking For Life is relational, financial, and existential self-help for the masked autistic — it’s the sequel to his first book on the subject, Unmasking Autism, which focused on describing all the marginalized autistic people who figured out how to get to adulthood and evade diagnosis by performing normal, at great cost to our health.

Devon estimates that ‘fewer than 10 percent of Autistic children who would be diagnosed today were diagnosed in the 1990s,’ which is a lot of undetected autistic people walking around out there, suffering and confused about it!

I realized when I saw this page in the book that I actually haven’t been writing much about autism for a while. There’s a couple reasons — for one, I just got interested in other things, like dopamine and drug shortages and compost and fatigue and blood brains and trans theology and bugs and Huberman lore, etc etc.1

For two, I really didn’t want to be an autism influencer, or an influencer at all. I’m a writer, and if I influence you, I hope it is in thinking more deeply, or differently. But another reason, I think, was the panic that I’d overshared.

“Most Autistic people default to being open books,” Devon writes (calling me out). On Instagram, I had memed through my struggle to get psychiatric care, and my horrible diagnosis experiences, and my autistic masking epiphanies during lockdown.

Quotes from a couple of my essays appear in Devon’s previous book, Unmasking 1 — pieces I wrote not long after I found out that I was autistic. I was doing that thing where you look back at the past through a different lens, and marvel at how it fits: why I drank so much, why I went to every social event with a camera in one hand and a charismatic partner on the other, why I was always fetal and sobbing even though my life, on paper, seemed fine.

It felt important that I share all of this, because memoir and personal essay have always been helpful mirrors for me, and I wanted to reflect something back. One of my favorite things about the autistic community is the obsessive tendency toward autie-biography — how much we share with each other, so we can see ourselves.

But then comes the horrifying realization that you are being widely seen, maybe before you have even figured it all out for yourself.

A couple summers ago, I had an encounter at a party. I’d been trying to leave for half an hour, but got stuck small-talking with a tiny blonde yoga teacher, who asked me what I do, to which I said, Write, to which she asked the logical follow-up question: What do you write about?

The world disability came out of my mouth automatically, and I quickly wished I could take it back.

“Oh! I used to work with people who have disabilities! It was so rewarding,” she said, her face lighting up. Oh no, oh no, oh no. Abort! Abort! I nodded and smiled.

She’d started explaining her role in some kind of health services job, and I was trying to balance my eye-contact-to-looking-away ratio so I could hear what she was saying, when she stopped and looked at me pointedly.

“But you know,” she said. “Some people have invisible disabilities.”

I kept nodding, well-aware, mine beginning to stab me behind the left eye, and she kept looking at me. Why did she stop talking? I was thinking. What’s that face she’s making? Expectant? She’s waiting for me to say something? “Some people have invisible disabilities”? And she’s looking at me… Oh no.

“Are you…asking…what my disability is?”

She nodded like I was a precocious child who had just correctly answered a math problem.

Oh fuck.

And just so you know, reader, you should never do this! Don’t ask people to disclose personal medical information to you! They’ll tell you if they want to! If they feel like you’re not gonna be weird about it!

This lady was definitely gonna be weird about it, and there are several ways I wish I had responded in this moment: “No, I’d rather not, thanks.” “I don’t feel comfortable telling you that, sorry.” “I’m going home now, goodbye.”

But I was hot, and sweating, and light-headed, so I didn’t say any of that. I felt pinned down by my own habits of concession, choked by my own shame.

Quietly, I mumbled, “Um, I’m autistic, and ADHD,” and her eyes burned with the fire of hot gossip.

“There’s something I have to ask you!” she said, lowering her voice a little and leaning in closer. “What do you think about this trend of kids diagnosing themselves with autism on the internet?”

Oh fuuuuuuuucckkk.

The mask was masking — on the inside, fire shot through every nerve in my body, my head felt like it was going to pop like a balloon and ooze all over the floor at any minute, and I was scrambling for words to say to this woman who clearly pitied disabled people and harbored suspicions about us.

But on the outside, I was calm, and rambling about the complicated politics of diagnosis, hoping it was boring and meandering enough that she would lose interest in me, but unable to end the interaction myself.

“Simply put, we are free when we are allowed to seem off-putting, and we may be imprisoned when we’re easiest to be around,” Devon writes (calling me out again).

When I finally found a way to grab the host, thank them, and say goodbye, the headache had spread across my face, and it stayed for three weeks.

“The project of unmasking is ultimately a question of values and priorities,” Devon writes. Once you’ve realized who you are and what you value, how do you live by it?

You have to give some stuff up — for me, at first, it was daily, heavy drinking. This made everything, from working to socializing, a lot harder. The aforementioned conversation would have gone very differently if I was drunk; I likely wouldn’t have even remembered it, which means I never would have learned anything from it, either.

Unmasking 1 helped me figure out that my greatest value is curiosity. I relish a question, and the thrill of trying to answer it. I live to find out more. But Unmasking 2 led me to the realization that the shadow of my curiosity is self-doubt. I tend to get stuck on unanswerable questions, ruminating.

In a chapter on planning to grow old and leave a legacy, Devon asks us to consider the question: ‘Where does too much of my time currently go?’

My eyes drifted to one short phrase at the bottom of the list. Questioning myself. Everything I manage to do, say, or put into the world struggles first through a dense cloud of what if, what if, what if. It is a storm that siphons off my energy, unanswerable questions that eat my days.

A couple winters ago, Marta and I were on the highway between New York and Philly, after taking a day trip to a weird little art event about attention studies, a topic I’d been fixating on.

It had snowed that morning and I almost didn’t go, because I had never driven on ice and I was terrified that if the tires slipped at all, I would freak out and slam the brakes and spin off the road and kill us both!

But then I learned about salt trucks and snow plows, and how major highways actually get salted first, so they’re safer than side roads, and I took a deep breath and packed my catastrophes into my backpack with me, and we went.

It was great, and I was feeling very accomplished to have faced my snowy fears, but my reprieve from the what-if storm is only ever short-lived. On the way back, the sun slipping past the smokestacks in Jersey, another worry slipped out.

“Sometimes I worry that I’m not really autistic,” I said.

“What!?” Marta replied, as if I’d just told her that pigs actually do have wings, you just can’t see them.

“Well, I don’t know. What if I’m wrong? What if I’m out here talking about autism all over the internet, when really I’m just traumatized, or OCD, or ADHD, or BPD, or bipolar? I know I spent years reading about it, and none of the drugs or therapies I tried really worked until I started taking advice from autistic people, and also, my brother’s autistic, so it clearly runs in my family, and everyone who’s really close to me is autistic, and I’m like, obsessed with critical autism studies and autistic memoir, but I don’t know! Couldn’t I always be wrong?”

“Honey,” she said. “You’re very autistic.”2

The poet (and masked autistic)3 Savannah Brown likens shame to a lucid dream. She says that in lucid dreaming, you have to teach yourself how to wake up inside the dream by learning to recognize a distortion, like how clocks never look right.

Brown knows she’s in a dream when she can’t read words — this clue allows her to wake up her awareness. Similarly, she ‘learned the tells’ of her shame, the way it distorted her view of the world:

“If I found myself ruminating on my social self, or nitpicking my words, or judging other people in a way that determined their worth or lack of worth, or telling myself I was stupid and weak for communicating, I’d say, hold on. I’m dreaming. And then I’d literally say, I am waking up in the dream of my shame. I am waking up in the dream of my shame.”

This is all very abstract and mystical — as poets are wont to be — but I see Unmasking 1 + 2 as pragmatic guides to waking up in the dream of your shame. It’s something I’m still figuring out how to do, to be honest. It takes a lot of practice when you’ve been living in that dream for a long time.

But Devon’s masked autistic guidebooks help me see myself in context — I am not having a unique experience, and that is comforting. His work is a gift to a population that frequently has to seek support outside the medical system, because we are the some people who have invisible disabilities — disbelieved, misunderstood, and overlooked.

His story-gathering and research-collating is an effort to make a mirror for us, to make us visible to ourselves, and to each other — and yes, that happens most often, for autistic people, on the internet. For Brown, the internet has been ‘a bit of a godsend’.

“I’m really grateful that we’re all here,” she says, “and that we’ve all found each other here.”

in unison, we chant: it’s all connected i promise. it’s all connected i promise.

one of my favorite descriptions of masking @ 8:19: “I wanted to die because I was exhausted. I was exhausted. I would go to school and act in my personal eight hour long play and be exhausted, and then I'd come home to my family and act in a second, angrier, eight hour long play, and be exhausted.”

Wow, I am both totally floored and flattered that you created this wonderful piece that converses so actively with the book, god do I love to see art in collaboration with other art, *and* I'm struck with the fact that by quoting from you in my books, I've denied you a bit of that opportunity to step away from the public eye when it comes to writing about Autism. The stories that we've told and the processing that we've both done out in public have both become these...things... that exist outside of us. I haven't always had the reigns on how much I share or where I share from, either. And it's hard sometimes to tell the difference between throwing back the veil of shame to be openly unabashed in oneself, and...searching for yet another way to try and dazzle and elide and over-justify my own and others' existence for an external audience.

So much of what you have written about neurodivergence and related topics has brought such clarity to me, where before there was only shame and confusion. It happens both in the little details that are so recognizable, and in your theoretical approach, which has given so many of us a new way of venturing into discussions about neurodivergence that weren't getting anywhere useful before. I'm very happy to see the conversation between our bodies of work continuing on in this way. I'm so lucky to know you!

“Sometimes I worry that I’m not really autistic,” I said. Hard relate. This is a layer of shame that exists outwith other layers of neurodivergent shame.