It's Not "ADHD Fakers" Taking All the Adderall

drug shortages are a feature, not a glitch [The Adderall Series part 3]

When my partner and I went to pick up our prescriptions at Rite Aid, the generic, immediate release Adderall they needed was out of stock. “We do have the extended release, though,” the pharmacist added, trying to help.

We spent a while at the counter deliberating, and finally accepted that there was nothing to be done except wait and hope for more to come in. After we got in the car, they turned to me and said, “Why is it always the generics out of stock?”

A very good question! When it comes to the Adderall shortage in particular, there are three common reasons that you’ll see given in the media:

Overprescription created too much demand

The DEA caps controlled substance production

The global supply chain got disrupted

All of these are certainly factors at play, but I don’t think any of them really explain the whole story — it’s the trees, but not the forest, because shortages are not rare anomalies in a capitalist economy. They’re a feature of markets dominated by massive, multinational corporations.

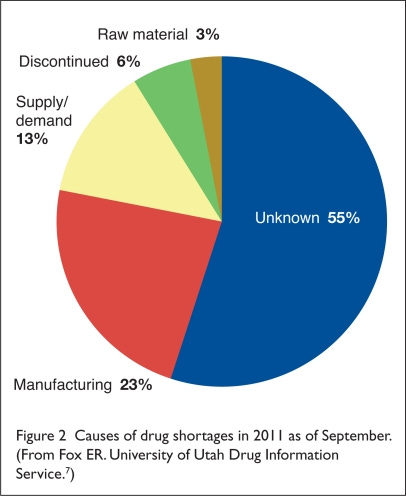

The pharmaceutical industry is notoriously opaque — it’s been estimated that 55% of drug shortages have an unknown cause, because companies are not required to tell anyone when or why they’re discontinuing a drug.

Global capitalism’s endless push for efficiency has led to shortcuts all over the place. In order to maximize profits, pharma companies operate with just-enough workers to make just-enough supply,1 which makes them extremely vulnerable to any sort of unexpected disruption, like say, a global pandemic, a war in Ukraine, a sharp increase in oil prices, or a rise in ADHD diagnoses.

Companies do not make extra drugs to prepare for these unforeseen problems because they could go to waste, and waste is the enemy of capital, but they will put out all kinds of other excuses to explain product shortages instead.

For example, Teva has been telling the media that their inability to manufacture enough Adderall was due to a “labor shortage”. In reality, the company has cut 14,000 jobs since 2017, most recently laying off 300 workers in August of 2022. They’ve been fighting thousands of opioid lawsuits and are set to pay out $4.25 billion in settlements over the next 13 years.

In February, Teva’s new CEO Richard Francis announced the company will be “reprioritizing” to “get back to growth”. This is important context, because Teva is the world’s largest generic drug maker, and Reuters reported in February that their 2023 forecast was disappointing for investors. Generics just aren’t cutting it, and Teva plans to prioritize developing more profitable “biosimilars” — specifically, a copy of the highest-grossing drug ever, arthritis biologic Humira, which went off patent at the end of last year.

Because there’s no law that says a company has to produce a certain drug, corporations can “deprioritize” cheaper generics all they want.

A recent FOX13 report tells the story of Rebekah, a mother who was forced to switch her child to a medication that costs 3 times more than Adderall, which she was only able to afford because the manufacturer offered a short-term discount coupon. The Baltimore Banner tells a similar story of a mother being forced to switch her daughter to brand-name Concerta which “cost $400 for a 30-day supply, compared to the usual $20-$30 copay for the generic”.

This profit-motivated problem is bigger than stimulants — it’s often the cheapest and most necessary drugs that end up in shortage, like the contrast media hospitals use to detect strokes, or antibiotics that can treat pneumonia. A 2011 paper describes what happened when a new version of a generic chemotherapy drug called leucovorin entered the market:

“…leucovorin has been available from several manufacturers since 1952. In 2008, levoleucovorin, the active l-isomer of leucovorin, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It was reportedly no more effective than leucovorin and 58 times as expensive, but its use grew rapidly. Eight months later, a widespread shortage of leucovorin was reported.”

They created the generic leucovorin shortage by simply making less of it, because a new version was bringing in more money. Maybe this sounds conspiratorial, but it’s really not. It’s just businessmen taking advantage of the way our economic system is designed.

Businesses are free to not make your medicine, just like they’re free to charge you more for eggs and pocket the change — corporations often report record profits during times of shortage and inflation, because they use them as an excuse to raise prices.

Pharma companies in particular use a number of tactics to manipulate the market for profit, as University of Utah’s senior pharmacy director Erin Fox explains in Harvard Business Review: they pay off other companies not to release generic versions of their drugs, submit “citizen petitions” to the FDA to stop them from approving certain generics, and flat out refuse to provide generic drug makers the samples they need to prove their products are just as effective as the brand name version.

Another way these companies take advantage of the system is by tweaking an old medicine to create a technically new, extended release formula that can be protected under patent. These are sometimes referred to as “me too” drugs, because they’re not really necessary when a cheaper version that meets medical need already exists.2 But extended release medicines are a lot more expensive — a study in JAMA found that they cost Medicare and Medicaid $14 billion more from 2012 to 2017 than their equivalent short-acting prescriptions.

You can see this happening right now with a new extended release amphetamine called Adzenys XR. Here’s a pop-up that immediately bombards you upon visiting the medication’s website:

At time of writing, a month’s supply of Adzenys XR cost $491 without insurance, where the generic version of Adderall XR costs around $60. The manufacturer is also offering a coupon to help subsidize the cost for new patients, a sales tactic which has been criticized for leading consumers away from cheaper generics and raising healthcare costs overall.

Aytu BioPharma, the company that makes Adzenys and an extended-release rebrand of methylphenidate called Contempla, reported a 24% increase in sales of its ADHD medications in the first quarter of 2023. Generic shortages, clearly, are good business for patent-holders.

This brings me back to common shortage reason #2 — the government cap on production, which has been in place since the Controlled Substances Act was created in 1971 and is reviewed annually based on prescribing data. Some are framing the issue as if the DEA limited production because too much Adderall was being prescribed, but that’s not how it works, according to Pharmacy Times:

“The only way that quota can be decreased is by a decrease in actual prescriptions dispensed…Prescribing behavior drives quota.”

In fact, the DEA’s quota notice for 2023 said companies who manufacture amphetamines have not fully used their allotted quota for the past three years. In February, Bloomberg reported this, from a DEA spokesperson:

“…at the end of 2022, manufacturers of Adderall as well as the drug’s raw ingredients had products on hand with at least 34,980 kilograms of amphetamine — about 83% of the total quota the DEA had allowed to be produced for the year..”

The same month, the CEO of Aytu BioPharma wrote an op-ed blaming the DEA quota for the stimulant crisis and citing an unprecedented rise in demand. The government and industry are basically just pointing fingers at each other, which happens every time there’s an Adderall shortage, but I think trying to assign blame to one or the other is missing the point, because they actually work in tandem to make drug shortages an unavoidable feature of a capitalist healthcare market.

Aytu’s CEO laments the “cumbersome red tape” that keeps controlled substances in short supply, but he doesn’t mention that red tape actually helps his industry maintain a very lucrative monopoly on stimulant drugs.

As law professor Mason Marks writes in STAT:

“When drug makers gain DEA and FDA permission to commercialize drugs that are otherwise illegal, prohibition shields them from potential competition. It strengthens government-granted monopolies provided by patents and marketing exclusivity.”

That exclusivity was enhanced with the passage of an international trade agreement called TRIPS in 1994, which basically forced over a hundred countries that previously did not have strict laws about drug patents to adhere instead to America’s rules, or else face trade sanctions. 3

Yes — US pharma companies use the government, quite literally, to protect their bottom line. And what’s even more infuriating: it’s been estimated that two-thirds of funding for drug research and development comes from taxpayers. Companies are then allowed to turn around and patent these drugs for profit thanks to the Bayh-Dole Act. As law professor Fran Quigley writes:

“The result is that private companies benefit from a process that socializes the risks of medicines research and privatizes its rewards.”

It’s easy for those in power to blame the stimulant shortage on some nebulous group of “drug-seekers” faking ADHD to steal all the Adderall, but scapegoating individuals for problems of the system, especially in order to deny widespread social welfare policies, is the oldest trick in the book.

A 2021 paper on the history of the malingering myth explains that the fear of people faking illness to access resources has deeply shaped social policy in the US, despite not being supported by any evidence:

While such fraud and especially health care fraud does occur, in virtually every case the malfeasant is a health care worker or health care organization defrauding government assistance programs or payors. In other words, the specter of hordes of “fakers” crashing social welfare regimes has no connection to the reality of benefit fraud in the US.

This old story about illness fakers taking resources from “deserving” patients is a convenient cover for corporations that makes it appear as if the stimulant shortage is totally out of their control. But there are plenty of economic reasons for shortages, and most of them have to do with, as Teva’s CEO said, “getting back to growth.”

What else can we really expect from a healthcare system more concerned about profit than health?

This part 3 of a series I’ve been writing about Adderall. See part 1 on the difference between Adderall and meth, and part 2 on self-determination and drug user solidarity.

this is called “just-in-time production”

see this paper on making medicines a public good by Fran Quigley

for a great analysis of how pharma companies and the US government work together to control the global pharma market through International Patent Law, see the Pharmacology chapter of Health Communism

This is a terrific piece. Thank you.

Wow I had no idea. Ughhh. What do we do?? Well I guess knowing the truth helps so we aren’t spreading lies that fuel all this lack of accountability...

I only read the abstract and table of contents for the medicines as public goods article and love it! What and who kind of people is needed to make that happen?