The Politics of Flow and the Experience of Hyperfocus

a critical dip into a positive psychology classic and a look at some new research

I had always assumed flow and hyperfocus were just different names for the same thing, but flow was framed as a superpower (Harness your flow state to achieve optimal performance!), and hyperfocus was framed as a deficit (Why can’t these autistic people stop talking about dinosaurs and get jobs??). But in the last five years, studies have begun trying to pull these concepts apart.

First: we must take a brief detour into the positive psychology best-seller Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

Mihaly Csikszentmihályi1 popularized the idea of flow in this 1990 book, which has been embraced by entrepreneurs and HR departments everywhere. Positive psychology, which prefers to focus on well-being rather than disorder, can be traced back to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in the 50’s, but it really picked up steam in the late 90’s, and has since been widely criticized for its tendencies to individualize social and political problems.2

You are likely familiar with these ideas already: reframing your struggles with positive thinking, using mindfulness to cope with capitalism, and implementing workplace wellness programs to improve a company’s ROI. They’ve all come out of this field, which views happiness as a choice a person can make by changing their mindset.

The manifestation girlies did not come up the idea that you choose your reality — it’s a positive psychology trope!

For Csikszentmihályi, flow is an immersive state that makes a person happy, fulfilled, and most importantly, productive. He described flow as a thing that happens when your skill level just barely matches the challenge in front of you, sort of like in a video game, when you die just enough times to make you want to keep trying, but not so many that you get frustrated and abandon the game entirely.

It’s a state of enjoyment and absorption that distorts your perception of time, your awareness of things happening around you, and even your self-consciousness — you forget yourself in flow, but at the same time, feel wholly in control.

Self-control is actually a major theme in Flow:

“The mark of a person who is in control of consciousness is the ability to focus attention at will, to be oblivious to distractions, to concentrate for as long as it takes to achieve a goal, and not longer. And the person who can do this usually enjoys the normal course of everyday life.”

Csikszentmihályi argues that controlling your attention to achieve goals is the path to happiness — a claim which I am immediately skeptical of, as someone who does not view achievement as the pinnacle of being alive — but you can see where positive psychology starts to get real politically sus in Flow’s anecdotes about factory workers.

In one example, Julio is worried about his flat tire and it’s distracting him from doing good work on the assembly line. He doesn’t have enough money or time to fix the tire (because of work!), but he fears that it will make him late and possibly cost him his job. Csikszentmihályi writes:

“..if Julio had had more money or some credit, his problem would have been perfectly innocuous. If in the past he had invested more psychic energy in making friends on the job, the flat tire would not have created panic, because he could have always asked one of his co-workers to give him a ride for a few days. And if he had had a stronger sense of self-confidence, the temporary setback would not have affected him as much because he would have trusted his ability to overcome it eventually.”

You could also say if Julio got paid more or didn’t need to spend a huge chunk of his monthly income on a car because he had viable public transit options, he wouldn’t have to ‘invest his psychic energy’ worrying about losing his job so much! But throughout the book, Csikszentmihályi views the psychological as a solution to material problems.

In another anecdote, he describes a man named Joe, a welder who worked in a railcar factory for thirty years, and used his interest in tinkering with machinery to learn how to do every job in the factory and never get bored.

After work, Joe goes home and does not rest, but continues to tinker, building an elaborate rock garden complete with custom sprinkler heads attached to flood lights that create rainbows for him at all hours of the day. Csikszentmihályi praises Joe for attending so diligently to his work and not ‘wasting’ his free time,3 unlike his coworkers, who he frames as psychologically lazy for perceiving their workday as something to suffer through until they can go out to drink it off in the evenings.

He proposes that Joe is a good example of an ‘autotelic personality’ — someone who operates from intrinsic motivation and transforms threats into ‘enjoyable challenges’. But the thing is: Joe sounds autistic as hell!

He has never trained in mechanics, but is able to learn how to fix anything he’s interested in. At one point, Csikszentmihályi says that the way Joe figures out how to fix a toaster is by asking: “If I were that toaster and I didn’t work, what would be wrong with me?” which is very much giving Temple Grandin imagining that she’s a cow in order to invent better cattle stations.4

If machinery is an intense interest for Joe, it makes a lot of sense that he’s been able to enjoy a job that his coworkers find mind-numbing. But this isn’t the case for most workers, and a lot of neurodivergent people have interests that can’t be capitalized on at all. Csikszentmihályi assumes that Joe’s joy comes from hard work on his attention, but doesn’t consider that maybe he’s just a monotropic person who lucked into a job that aligned with his interest.

Self-discipline is a central theme in Flow — Csikszentmihályi thinks that if you work hard at your attentional skills, you should be able to enjoy any job, and he argues that workers’ dissatisfaction and stress, which he concedes are objective problems, can be addressed through ‘a subjective shift in one’s consciousness.’

“People who learn to control inner experience will be able to determine the quality of their lives,” he writes, “which is as close as any of us can come to being happy.”

So: if the concept of flow is about learning to control the mind to achieve whatever ‘happiness’ is, then what of hyperfocus?

Mostly emerging from anecdotes, it’s not really well-defined in the literature, but researchers are working on it. Hyperfocus is difficult to study because it’s hard to get someone absorbed in an interesting task in a laboratory setting.5 Recent studies have used questionnaires and interviews with neurodivergent people to get a better understanding of hyperfocus experiences.

In 2022, Grotewiel et al assessed a small group of college students with and without ADHD, and their findings suggested that ‘the defining difference between hyperfocus and flow’ might actually be control.

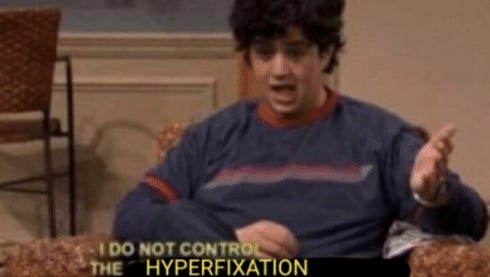

Hyperfocus ‘may be experienced as uncontrollable and jarring,’ they write, and I think immediately of my favorite meme on this subject, which I repeat to myself every time I accidentally spend days obsessing about something completely irrelevant to everything else in my life:

They also ponder the possibility of a flow continuum — a ‘seminal’ study on hyperfocus from 2019 proposed that it might be a state of ‘deep flow,’ somewhere at the extreme end of an immersive experience spectrum. As even Csikszentmihályi the positive guy noted, ‘nothing in the world is entirely positive,’ and researchers have found that hyperfocus can have considerable downsides.

A study from March of this year by Dwyer et al looked at autistic, ADHD, and AuDHD groups and found that it’s ‘sometimes beneficial, sometimes bothersome, depending on context,’ and was correlated with anxiety, depression, hypervigilance, and rumination.6 A 2023 study by Rapaport et al on a small group of mainly white, highly-educated autistic women identified three themes in their ‘task immersion’ experiences: total absorption, getting ‘to be me’ without judgement, and a struggle to find balance.

These participants also described hyperfocus in a more nuanced way, noting that they felt ‘regulated’ and ‘stable’ when immersed, but that it can create ‘chaos’ in the rest of their lives by getting in the way of stuff like homework, chores, and basic needs, even sometimes leading to meltdowns and burnout from an inability to disengage.

The main thing I take away from this research is that hyperfocus is both a joy and a pain. It’s not a superpower, although you can see how the productivity jargon of the flow state has leaked into neurodiversity discourse there.

“What if you could use hyperfocus on command, bend it to your will, own it, and make it yours?” ADDitude Magazine asks, suggesting the painfully obvious: Checklists! Alarms! Turn off your phone! (We know!)

But the thing about hyperfocus is that it often eludes these strategies, because it’s triggered by interest, and it’s very hard to fake yourself into interest that isn’t genuine. Interest, too, doesn’t necessarily align with productivity goals — it’s rewarding because you like it, an end in itself.

Csikszentmihályi does say this about flow, by the way — but then he argues that you can discipline your intrinsic motivation for extrinsic purposes, like working a job for someone else, which doesn’t make much sense to me. Flow takes these ideas about self-discipline into some ableist territory: at one point, he describes a woman who he claims recovered from a chronic illness by ‘disciplining her attention and refusing to diffuse it on unproductive thoughts or activities.’

But what if you can’t bend hyperfocus — or your health — to your will? What if your attention is not a resource to be tapped, but a relationship with the world around you?

Conceptually, I think of flow and hyperfocus as different lenses on the attention tunnel experience. Csikszentmihályi’s flow can be a sort of ‘cruel optimism’,7 viewing attention as ‘an energy under our control, to do with as we please’, something we must optimize for the sake of achievement.

The hyperfocus neurodivergent people describe tends to be more realistic, accepting the ‘sometimes beneficial, sometimes bothersome’ nature of immersion, and the fact that our bodies and minds can’t always be controlled.

But I don’t know: what do you think? Is flow different from hyperfocus in your body? Can you control the hyperfixation? What does ‘happiness’ even mean???

pronounced: chick-sent-mee-high

There is an entire section in Chapter 7 called ‘The Waste of Free Time’, where he basically argues that people only think they like free time but actually hate it, and think they hate work but actually enjoy it..

I imagine that Grandin might also love positive psychology…

They are careful to note that this doesn’t mean hyperfocus is the sole cause of such distress, but that neurodivergent people experience more social alienation and oppression, which a tendency to hyperfocus could exacerbate. Intense interests can make it harder to find shared interests with friends, for instance, and hyperfocusing on a negative experience could become rumination.

Lauren Berlant defines ‘cruel optimism’ as desiring something that actually destroys you.. so like, that sense that if you just keep hustling, one day you’ll get the American Dream, except all the hustling also like, kills you faster.

Seems like a pretty classic case of differentiation for the sake of the larger argument to me aka capitalist endless productivity= good, neurodivergence that doesn't submit to the increase of capital =bad. That being said, as an ADHDer who has struggled with the difficult sides of monotropism, I've found mindfulness practices to be really valuable and it's hard to explain why it feels different from positive psychology sometimes. In my experience there's a tangible difference between being told that I should focus and invited to pay attention. When I try to explain the latter to other people or even to myself, it sometimes sounds like positive psychology because observing how I feel can change the way I feel with a result that looks a lot like "just think positive and make the best of your material circumstances". Not sure what to make of that in this context or how to talk about it in a way that doesn't sound preach-y and "manifestation"-y * shrugs *

hyperfocus feels to me more anxious, more like a grip, a compulsion. Flow can actually be relaxing and full of easeful clarity. I usually feel energised after I've been in flow and exhausted after hyperfocus.