Distracted By The Dopamine Slot Machine

dopamine dispatch #5: "digital fentanyl," technology panic, and what's really wrong with the internet

You thought I forgot about the dopamine dispatch, didn’t you? You were like, there goes Jess again, abandoning another new project, scattered pieces of a new idea left to drift unfinished in the void forever! Well, I didn’t!!!!! And you can listen to me read this one!

First of all, I love the internet, and you will pry it from my cold dead hands, you neo-puritans! Every day I fire up the old meme machine and find something that restores my faith in the creative power of humanity, like Americacore and epic ballads for short kings. However: as someone who is writing this very newsletter because my use of Instagram became so compulsive it was causing me both mental and physical pain, I have also felt the internet’s dark shadow.

But is it “digital fentanyl” as Republican Congressman Mike Gallagher keeps calling TikTok? Do glowing screens “turn kids into psychotic junkies,” as the psychologist Nicholas Kardaras wrote in a viral New York Post article seven years ago? Is the internet making us “a fragile, brain-dulled, Weeble-like, poorly postured, no-eye-contact, couch potato species,” as he argued in his 2022 book, Digital Madness??1

I think that’s a bit much, Nicholas, but politicians are certainly taking note of such digital doomsday cringe. In October, 42 attorneys general filed suit against Meta, alleging that they violated the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act and purposely addicted children to Instagram using a variety of harmful psychological tactics like “dopamine-manipulating recommendation algorithms.” The State of Massachusetts is arguing that Meta “has placed an undue burden” in the form of “increased health care expenditures” on mentally ill kids.

This week, the CEOs of Meta, X, TikTok, and Snap were called to testify in Congress about how they handle child safety on their platforms, with The Verge reporter Adi Robertson calling lawsuits “the big theme.” This tracks with bills currently on the docket like the Kids Online Safety Act, which would give states the power to sue social media companies over content they deem harmful to kids’ mental health.

The problem is that what counts as “harmful” depends a lot on your party lines — you can imagine how easily this could become straight up censorship in a place like my home state of Florida, for instance, which has been using concern for the mental health of kids to ban books by Toni Morrison and pass the worst anti-trans laws in the country.

This is complicated, and I want to be clear that I do think there are serious issues going on here. Social media companies absolutely are exploiting users for profit at any cost, including our health and privacy, and plenty of young people themselves are at the forefront of these fights against tech companies. But are lawsuits that draw on shitty histories like America’s many racist drug panics and the “debt burden” framing of disability really the best way to address the structural harms of Big Tech?

We Have Been Here Before!

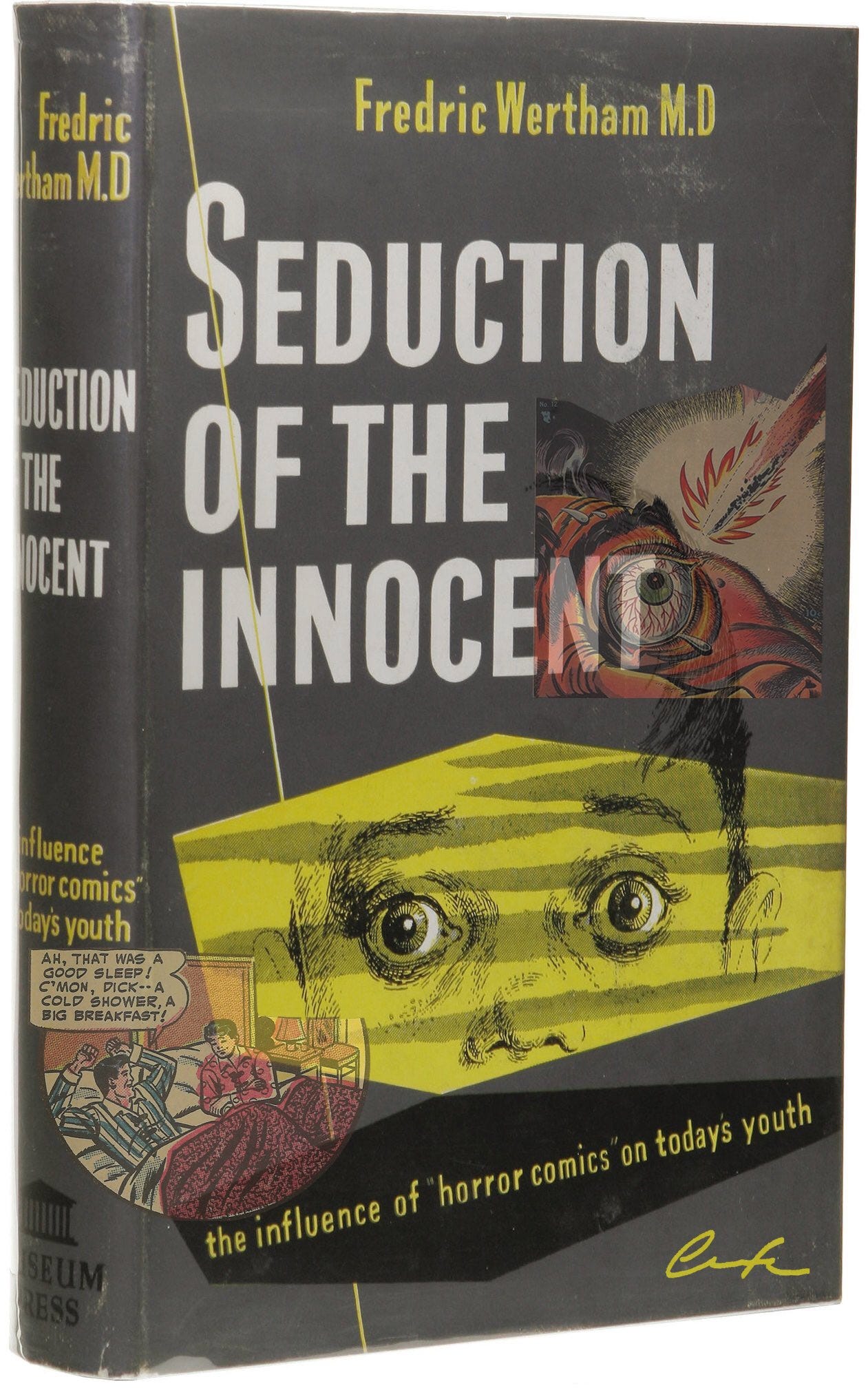

As the researcher Amy Orben explains, scientists have become a source of comfort for social anxieties, providing “a sense of security through the production of tailored research.” In a paper called The Sisyphean Cycle of Technology Panics, Orben points out that novels, radio, and movies have all inspired analogies to drug addiction and fears about disturbed children. For example, take the 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent.

Psychiatrist Fredric Wertham argued that comic books were causing “children’s maladjustments” through “chronic stimulation, temptation and seduction.” His testimony in Congress led the comic book industry to create strict rules around what kind of content was allowed to be printed, and numerous states passed laws restricting comic book sales. Wertham’s clinical notes were not available for public review until 2010, and when researcher Carol Tilley sifted through them, she found that he, um, kind of made a bunch of stuff up!

Wertham cherrypicked statements from interviews with children he treated and twisted them to fit his narrative. He thought Batman and Robin were turning boys gay, Wonder Woman was giving girls “violent revenge fantasies against men,” and that comic books in general drove kids into prostitution and the drug trade. Wertham based a lot of this book on subjects from a low-cost clinic he founded in Harlem, where the majority of patients were Black and Brown youth who had been diagnosed with behavioral disorders — what Tilley describes as “a catchall diagnosis that included truancy, shoplifting, and daydreaming.”

This means that in his narrow crusade to prove that it was a media technology like comic books causing crime and not, you know, the devastating effects of racism and poverty on children, Wertham erased the material problems of his subjects to fight an ideological threat.

Orben points out that, despite regulating comic book content, the “adolescent aggression” Wertham was concerned about is still fretted over today — only now, we’re blaming stuff like video games, social media, and smartphones for it. The academic term for this is technological determinism, the idea that new tech is the sole cause of large changes to society. It’s sort of impossible to determine simple causation like this when you look at history — in terms of social change, it’s more a clusterfuck of complex processes all happening at once for many reasons than a clear line from cause to effect.

Techno-determinism, however, tends to view humans as passive recipients of the shaping power of tech, instead of actors with agency who are shaping tech right back. So, the cycle of tech panic continues, over and over like poor old Sisyphus running up that hill. “The focus of concerns shifts to a new technology as society simply moves on,” Orben writes. Or, as Senator Thom Tillis said of the Tech CEO Hearing in Congress this week: “Every year, we have an annual flogging.”

Which Brings Me Back To Dr. Nicholas

Digital Madness is a strong contender in the running for my Pop Psych Hate-Read of 2024. I mean look at this fucking subtitle, giving me a BREAK, NICHOLAS:

Society-wide shifts in mental health involve a bunch of “wicked problems” feeding into our bodies and coming out as pain,2 but lawsuits and save-the-children legislation provide politicians with concrete accomplishments they can point to when they ask for votes, and medical professionals have come to play an important political role here.

As Orben points out in her paper, a psychologist can build a very successful career on the back of a technology panic that “guarantees funding, societal importance, and public attention.”

In my opinion, Kardaras is a particularly egregious example of this — in addition to his two books on the subject, he also owns three rehab centers that treat “technology addiction.”3 Let me know in the comments if you want a review of the absurdity in this book, but for now, allow me to direct your attention to a section in chapter five called The Sociogenic Trans Effect, wherein Kardaras throws his credentialed weight behind the popular conservative theory that the internet is transing your kids.

He cites a now-infamous study by Lisa Littman that claimed the existence of a phenomenon called Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria, based entirely on parent reports. “It is also important to note,” Kardaras writes, “that this reliance on the parents’ perspective has been one of the biggest criticisms of her study.” This is the understatement of the decade, Nicholas!

While any astute reader of LGBTQ history will recognize this as a rehash of the early 20th century idea that homosexuality was socially contagious, writer and biologist Julia Serano did a deep dive into the digital history of ROGD specifically, tracing it back to a website run by anti-trans parents called 4thwavenow.

In February 2016, a blogger named skepticaltherapist started to float the idea, comparing trans kids posting on Tumblr to an episode of Star Trek about an alien mind-control virus spread by a video game. “That is what this trans madness feels like to me,” the blogger wrote.4 Five months later, Lisa Littman — an ob/gyn who, at that point, had zero prior experience in trans healthcare — posted a call for study participants on 4thwavenow.

The problem, though, is that she only solicited study participants from 4thwavenow and two similar websites where parents of trans kids would meet up to discuss their absolutely heinous opinions about trans people. This is really, really bad study design, as Serano points out:

“Littman's survey & study appears to have been tailor-made to *confirm* the ‘transgender social contagion’ narrative, rather than to critically examine or test it.”

Professionals who endorse Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria have given anti-trans groups a sheen of scientific legitimacy that is helping them push through all kinds of prohibitive laws, from healthcare to free speech.

KOSA, the bill that is supposed to protect kids’ mental health online, was sponsored by Senator Marsha Blackburn, who told a reporter last year that she thinks the most important issue conservatives should be worried about right now is “protecting minor children from the transgender in this culture and that influence.” The anti-LGBTQ Heritage Foundation endorses KOSA by saying, “If we seek to protect kids online, we must guard against the harms of sexual and transgender content.”

Experts at the Electronic Frontier Foundation are pretty sure this bill is unconstitutional, and could end up dragging all kinds of important resources for marginalized groups off social media platforms. And it’s not just KOSA — there are a slew of “bad internet bills” on the table right now that follow in the footsteps of FOSTA-SESTA, the 2018 bill that was supposed to target sex trafficking but actually just turned social media extremely prude and made sex work much more dangerous.

Laws like these threaten digital rights by beefing up surveillance and censorship instead of creating comprehensive privacy laws that would protect all of us from the predatory companies getting rich off our data. There have to be ways to mitigate the harmful effects of algorithmic platforms on our health without giving Big Tech even more unjust power over our lives.

What If We Smash The Walled Gardens Instead?

In the novel Walkaway, Cory Doctorow describes a future where it has become possible for computers to fabricate anything we need. In this world, groups of people decide they are sick of living under the thumb of corporations, and simply walk away from what they call “default” society to build communities that create abundance with technology. No one owns anything, because they have everything, and if anyone gets possessive and weird, the walkaways just leave.

It’s a creative illustration of Doctorow’s vision for the internet in his new book, The Internet Con: How To Seize The Means of Computation.5 He’s skeptical of the idea that Facebook users, for instance, continue to use Facebook even though they hate it, simply because they are addicted to it. It does sound very similar to the way people talk about being powerless over their addictions, he writes, but the actual reason we keep using social media platforms that make us miserable is because we are effectively trapped in them — we can’t walk away.

Antitrust law has been whittled away since Reagan’s presidency, Doctorow explains, making it possible for a few corporations to dominate the market and hold both your social network and your data hostage in digital “walled gardens.” We don’t leave these walled gardens because if we did, we wouldn’t be able to keep in touch with our network anymore. Because of this, we put up with a lot of garbage advertising and algorithmic abuse, a process he calls “enshittification”.

Social media companies don’t allow us to exchange data between platforms — called interoperability6 in technical terms — because it’s bad for a business model where your attention and engagement are the exploitable resources. When I stopped using Instagram, I lost contact with a lot of internet friends I used to chat with on a regular basis, many of them living in other countries. The only way for me to continue talking to them was to log back into IG or get their phone numbers so we could What’s App — which isn’t really switching, because Meta owns that, too!

You know how you can’t use an app on your iPhone unless it’s been added to the App Store? You’re also not allowed to use a bot to scrape messages from your IG account and put them somewhere else so you can respond to them outside the app. To be clear, it’s not because that’s not possible — it’s just because it’s illegal, for business reasons.

Tech companies use “digital locks” to keep users locked in, and Doctorow goes into detail about how a small section in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act actually makes it a federal offense to bypass these locks and use third-party alternatives. Doctorow’s book gets deep into the weeds on regulations and standards, if you’re interested in how changing all this would work, but TLDR, it’s extremely boring stuff that nobody ever pays attention to because screaming about “dopamine hijacking” is way more exciting.

“It is precisely because this stuff is so dull that it is so dangerous,” he writes.

Those “dopamine-manipulating recommendation algorithms” cited in the lawsuit against Meta are harmful to our health because they are designed to maximize targeted ad revenue at all costs, so why not regulate that instead?

In The Smartphone Society, Nicole Aschoff argues that making it illegal to buy and sell our data without consent, while considered a “utopian” ask, could actually address a lot of our problems very quickly. And the EFF agrees in their critique of KOSA, saying that comprehensive privacy legislation would “protect children immediately by limiting the amount of data that companies can collect, use, and share about everyone”.

In her book, Aschoff shows how smartphones are a multifaceted tool — they have simultaneously become a detriment to workers’ rights in the form of gig economy apps, and a crucial means of organizing mass movements.

Just look at the global protests happening against the genocide in Gaza, despite a sophisticated multi-million-dollar propaganda campaign by Israel to suppress dissent. Public opinion has turned on this issue, in large part, because Palestinians’ tweets, posts, and livestreams of what’s happening to them in real time have been shared and amplified across social media.

“Technology isn’t the problem,” Doctorow writes. “Stop thinking about what technology does and start thinking about who technology does it to and who it does it for.”

This book is a gold mine of ridiculous quotes like this. Here’s another one: “In essence, a person is getting the equivalent of a brain orgasm every time they play a video game.” GUESS WHO HE CITES MULTIPLE TIMES, YOU GUYS? YEAH IT’S ANNA LEMBKE OF COURSE IT IS.

Stuff like: not having a stable job, dealing with gun violence, pandemic grief, incarceration, housing insecurity, a concerning lack of meaningful connections, a hopeless lack of purpose in your life, the ongoing genocide on TV, the threat of a third world war, the rapidly accelerating heat-death of the planet, etc etc etc

Putting this in quotations because it is not an official term, and addiction means something very specific in a medical context. The fact that smartphones and video games can be used compulsively is not really in question, but there is a lot of debate about terminology and what’s actually going on here — it’s a “conceptual minefield,” as they say.

Serano highly suspects it’s some psychotherapist named Lisa who loves Carl Jung!!

This guy is prolific — I read an interview where he said he wrote FOUR BOOKS and FOUR NOVELLAS in 15 MONTHS. Absolutely unhinged writerly behavior, could not ever be me, but I do respect the passion.

An example of this is how you can email anyone from your Gmail account, even if they don’t use Gmail, in contrast to Instagram, where you are locked into the app’s specific messenger

as a parent of a child, I have been trying to be transparent with her about my own endeavors to notice when my internet use is supporting me or when it is going beyond my ability to metabolize or integrate anything in intaking. it's an ebb and flow, I want to help model that for her rather than just cutting her off from the process of learning that herself by policing her internet use. policing doesn't get us anywhere, and I think the lawmaking route doesn't really empower people to learn about thier own nervous systems thru trial and error

Fantastic, as always!

I had a visceral reaction to the chapter in Karderas's book on "The Sociogenic Trans Effect." I suppose the groundwork has always been there to merge the "technology is harming the youth" camp and the "kids are being convinced they're trans" camp, but it terrifies me. I see the former being a pathway into the latter for those who don't know any better, because the former has widespread appeal and also some truth to it. I think of my dad, who is a smart, progressive person but also a fan of Huberman and Dopamine Nation because he's kind of an optimize bro - I could absolutely see him reading that book and not completely dismissing that chapter, although I'd hope he would be skeptical because he knows me (I'm trans) and has had to learn about trans people long before the most recent "trans panic."

Also for some reason Substack app isn't letting me copy text but there was a line at footnote 2 that I thought was so so wonderful, where you essentially explained the rise in mental health problems as a function of a bunch of wicked problems, etc. I want to memorize it so I can quote it constantly. I cringe when people bring up the "mental health epidemic" or talk about how "we need better mental health care" - people tend to think individuals are just more broken and if we could just get everyone into therapy, all would be well. As a therapist, I would argue that's not true. MOST of the things that are harming people I can do nothing about, other than sit with them in their pain. Would it be great if everyone could access therapy? Absolutely. But it would not solve the "mental health epidemic."

Also, I would totally read a summary of that dumb book because I can't hate read things (too stressful) and know thine enemy etc. and genuinely I'd read anything you wanted to write on the subject!