ADHD Consciousness, Brain Wrinkles, and Life-world Disruption

Two recent ADHD papers and one classic about the philosophy of chronic illness

Let’s try a new format, because I am literally allergic to doing the same thing for too long, sorryyyy!

I once polled my audience and a reader asked if I would do round-ups but for research papers, and I thought that was a very good idea, since I am always sifting through papers for some reason or another and finding interesting stuff.

These aren’t necessarily going to be new papers, although some might be, but, you know..

Do Stims Make Your Brain More Wrinkly?

I haven’t done a social media debunk in a while and I know it’s always a crowd-pleaser, so here we go: this video came across my fyp recently, claiming that a new study has now proven that ADHD meds “can actually improve brain structure.”

This is not really what the study found or what the researchers concluded, and I actually had a very different takeaway after reading through it. The study is called:

📝 How psychostimulant treatment changes the brain morphometry in adults with ADHD, Ghozy et al, 2025

Researchers pulled the brain scans of 26 ADHD adults from a pre-existing database. Half of them had been treated with stimulants, and half had never taken them — they compared these groups’ brain scans and symptom scores.

The group of 13 people that had taken stimulants included three different types, various dosages, and also different durations, from 1-5 years.

They found that the medicated group had more wrinkles in their brains (higher gyrification index), deeper wrinkles (increased sulcal depth), and more complex shapes on their brain surface in the frontal lobe (higher fractal dimension).

But, the untreated group also had more complex brain surface shapes, just in a different part of their brains.

The only clinical difference they found was higher ‘venturesomeness’1 in the untreated group.

Despite finding differences in the brains of the medicated group, they did not find any changes in their symptom scores.

This is a crucial point that the researchers state in their abstract, but the creator failed to mention. They suggest showing this study to people who argue that ADHD medication is ‘bad for the brain’, but I actually think that could hurt your case, because this particular study found that stimulants were associated with brain differences, but not improved symptoms!

Which, of course, doesn’t mean they’re not extremely helpful for some people, sometimes!2 But it makes me think of something Awais Aftab wrote recently about this:

Don’t take stimulant medications because you believe that you have a defective brain and you need the medications to fix that. That’s a terrible reason to stay on stimulants! If you were told that by a clinician, you were told an oversimplified story that you should give up. Take stimulants if they meaningfully improve your life and allow you to function better — regardless of whether ADHD is a “medical disorder.” Take them as long as they do, and if you find that your life is better without them, that’s okay.

What is ADHD Consciousness?

While we’re on the subject, I found this ADHD4ADHD theory very interesting. It’s by a psychotherapist with ADHD, and it’s an alternative to deficit-based, cognitive behavioral theories based on interviews with ADHDers about their experiences:

📝 The Creative Awareness Theory: A Grounded Theory Study of Inherent Self-Regulation in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Champ et al, 2024

Champ found that the ADHDers she spoke to described being in constant motion between two states: chaotic attention and hyper focus: “..it was difficult for them to describe one state without relation to the other.”3

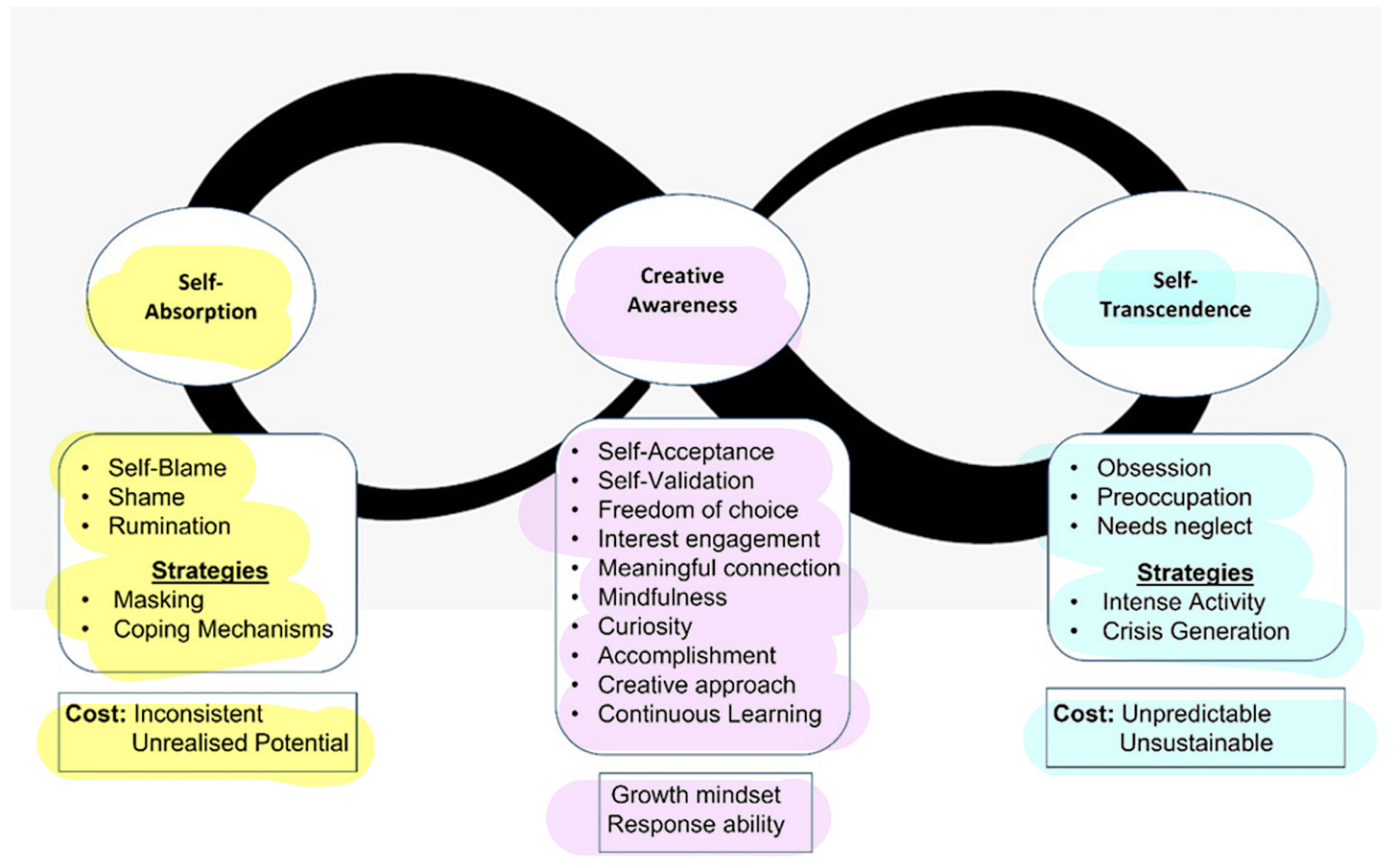

The paper outlines three different self-regulation strategies that are used to navigate these two states of ‘ADHD consciousness’: self-absorption, self-transcendence, and creative awareness

Self-absorption strategies try to deal with chaotic attention through masking and (maladaptive) coping mechanisms

There’s a sense of the self as ‘dysfunctional’, ‘broken’, ‘ a failure’, lots of ‘self-blame, shame, and rumination’, and ‘anxieties around rejection and lack of hope’

“Participants aimed to gain a sense of self-control by actively engaging in negative self-criticism, withdrawal, and isolation”

While these strategies do sometimes help manage chaotic attention, they cost a lot of energy and harm a person’s self-esteem

Self-transcendence strategies attempt to deal with hyperfocus by letting it take over and using it to finish tasks, or relying on ‘crisis generation’ like deadlines or high-pressure situations for motivation.

This can lead to crashes, overwork, and self-neglect (ie not eating or peeing because you’re stuck in the focus tunnel). These strategies also use up a lot of energy and neglect a person’s needs.

Creative awareness strategies exist in the sweet spot between self-absorption and self-transcendence, basically becoming aware of ADHD traits and learning to accept them, using curiosity and mindfulness as tools to navigate the two poles of attention, and developing an ‘authentic inner compass’ in order to cultivate intrinsic motivation, not goals that come from outside.

How Does Chronic Illness Change Your Life?

Intellectually, I’ve been on a bit of a chronic illness kick lately (coping mechanism), and in a book on contested illness I explored last week for paid slugscribers, I discovered the work of disabled philosopher S. Kay Toombs, who writes about how chronic illness is fundamentally different from acute illness, and what that means for the doctor-patient relationship:

📝 The Metamorphosis: The Nature of Chronic Illness and Its Challenge to Medicine, S. Kay Toombs, 1993

In chronic illness, ‘the body opposes the self’

Most of the time we don’t have to think about our bodies, but in chronic illness, you gotta think about your body everyday. There is a sense of being ‘inescapably embodied’.

Toombs argues that chronic illness is different from acute illness because it is a kind of metamorphosis where ‘the experience of bodily disruption becomes one’s normal expectation and non-disruptive moments appear as only fleeting anomalies’

Chronic illness disrupts both space and time: ‘One can never be certain, from one day to the next, as to the extent of one’s physical capabilities’

In acute illness, disease is seen as an ‘external threat’ that has to be ‘defeated and banished’, but this doesn’t work for chronic illness, where disease ‘becomes an intrinsic element of one’s being’

“The goal for chronically ill patients is to learn to live disordered lives”

Chronic illness also challenges the typical doctor-patient relationship, where a patient gives control over to the doctor to heal them. Patients often have had to learn a lot about their bodies and their illnesses, which means ‘each must trust the other’s knowledge as they work together in the therapeutic endeavor’

“Healing is a mutual act”

Toombs recommends that doctors don’t just focus on the disease process, but that they also ask patients questions about their ‘life-world disruption’ (ie ‘what is the most difficult aspect of your illness?’ and ‘what do you fear most about this illness?’)

These conversations can be therapeutic, because they can prevent the patient from feeling ‘abandoned’ by medicine or ‘beyond help’

Okay, that’s it, short and sweet and full of bullet points like a newsletter is supposed to be. Let me know if you like this segment, and I’ll keep doing them!

described as ‘awareness of the risk and doing it anyway‘

and it also doesn’t mean they’re ‘bad for the brain’ — everything changes the brain. If you think brain changes are scary, then you better not learn anything new ever again!

The authors missed a great opportunity to title this paper, Inside You Are Two Wolves: Chaotic Attention and Hyperfocus

“The authors missed a great opportunity to title this paper, Inside You Are Two Wolves: Chaotic Attention and Hyperfocus”

They really did. My first thought too!

Great idea for a segment, a fulfilling knowledge snack.

Oh my god I loved this format so much!!! The studies you chose to review are definitely ones I would love to read and appreciated having summarized.