Time-Lapse Blues

on speed as a drug and choosing to go analog

Lately when I think too hard, it’s about rhythm and time. I’ve been making more videos (haven’t we all). I’ve been dipping my toes in and out of internet feeds, just to see how it feels on both sides. I keep getting time-lapse videos of people painting stuff at 10x speed.

You know the ones, where artists show you their process, or someone documents a DIY project. I love them. They look how I imagine effortlessness would feel, if it existed. These videos satisfy something in me that needs to be instantly gratified, but they also make me feel deeply inadequate.

Look how easy it is to paint your living room! they seem to say. Why did it take you three months?

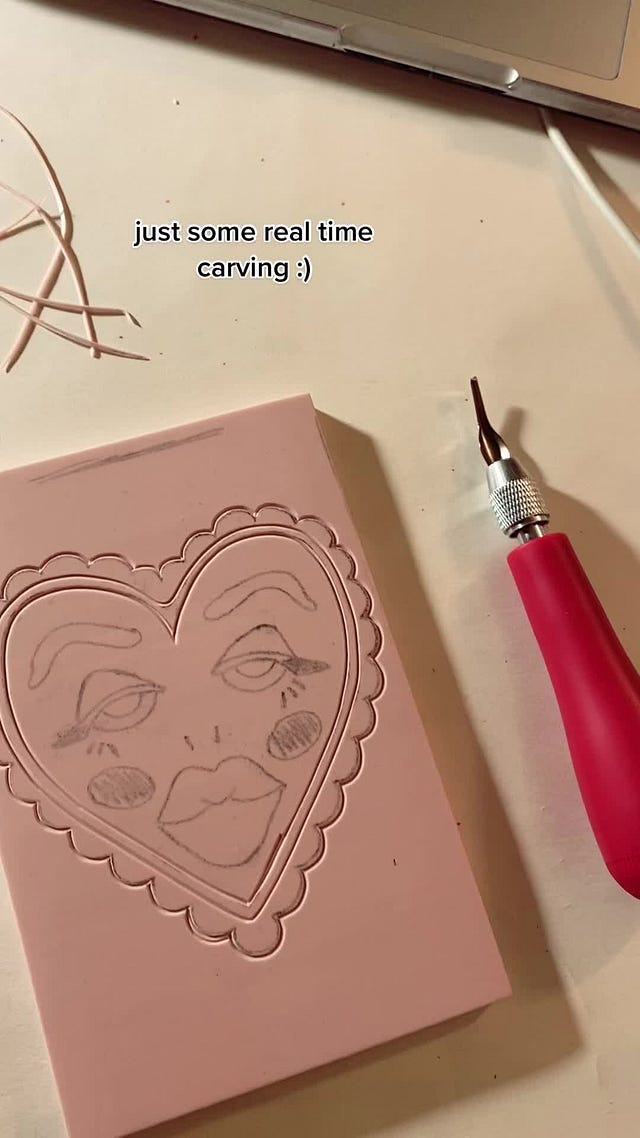

In between the time-lapses, I came across a video of someone carving a design out of a block of linoleum in real time, and it was painstakingly slow, almost unwatchable. But I realized: this is the phenomenon of art-making that we compress for the internet. It’s not quick and satisfying, it’s incremental, and a lot of the time, honestly, it’s pretty boring.

Time-lapse videos collapse time, giving us the impression that creating is easy. To stand in the slower rhythm of Real Time and peer down into hyperspeed in our hands is disorienting; it instills a sense of creative lag. It’s not just unrealistic expectations of our bodies’ image that social media creates, but its abilities, too.

We feel that our lives are dragging; our work is behind; the pain of making is unique to us. We feel that it shouldn’t be this hard. I say feel on purpose — because of course, we know that all creative projects take a lot of time and effort, that it’s never a neat, A-to-B process. But feeling settled in the maw of slow, steady Real Time is another thing entirely.

I find myself longing for a confession in the caption of these deceptive time-lapses. This video took two weeks, three days, and seven hours to make. I cried at least twice, and made the following mistakes.

We cut the time out of our process like we curate the failure out of our feeds — we have to, because no one wants to watch you paint for five hours. Attention is time is money, baby. I long to bask in the illusion of quick and easy, but when the time-collapse ends, I am left frustrated in the glacial river of Real Time.

The more time I spend creating things on a computer screen, the more I find myself wanting to make something with my hands. It’s funny how going fast can make you regress. When I was learning photography, I wanted nothing to do with analog printing processes — I thought it was ridiculous to learn a dying art instead of Photoshop. But after years of hosing down my brain with hyperspeed everyday, I am starting to get it.

In a 2017 interview on what he calls speed-space, the architect Paul Virilio observed that film-making has entered an era of intensiveness. As image quality improves and internet speeds go faster, we’re smashing massive amounts of image data into ever shorter clips. He said:

Until the invention of photography, there was only an aesthetics of appearance. Images only persist because of the persistence of their medium: stone in the neolithic era or in ancient times, carved wood, painted canvas. … Those are an aesthetics of immersion, of the appearance of an image which becomes permanent. The image is sketched, then painted and coated, and it lasts because its medium persists. With the coming of photography, followed by cinematography and video, we entered the realm of an aesthetics of disappearance: the persistence is now only retinal.

Where a painting is a thing made of oil and canvas, there’s no object you can hold on to with digital images. You see it, and then it’s gone. High-definition videos, in particular, show us 30-60 images per second — disappearance at hyperspeed. The images flash so quickly, one after the other, scrolling, scrolling, scrolling, until you can’t remember a thing.

“Speed is a drunkenness, a drug,” says Virilio, and I feel it in the existential hangover I get after a few hours of chugging TikTok videos. The feed wipes my brain clean, churns my thoughts to mush, and kicks my nerves into abstract frenzy.

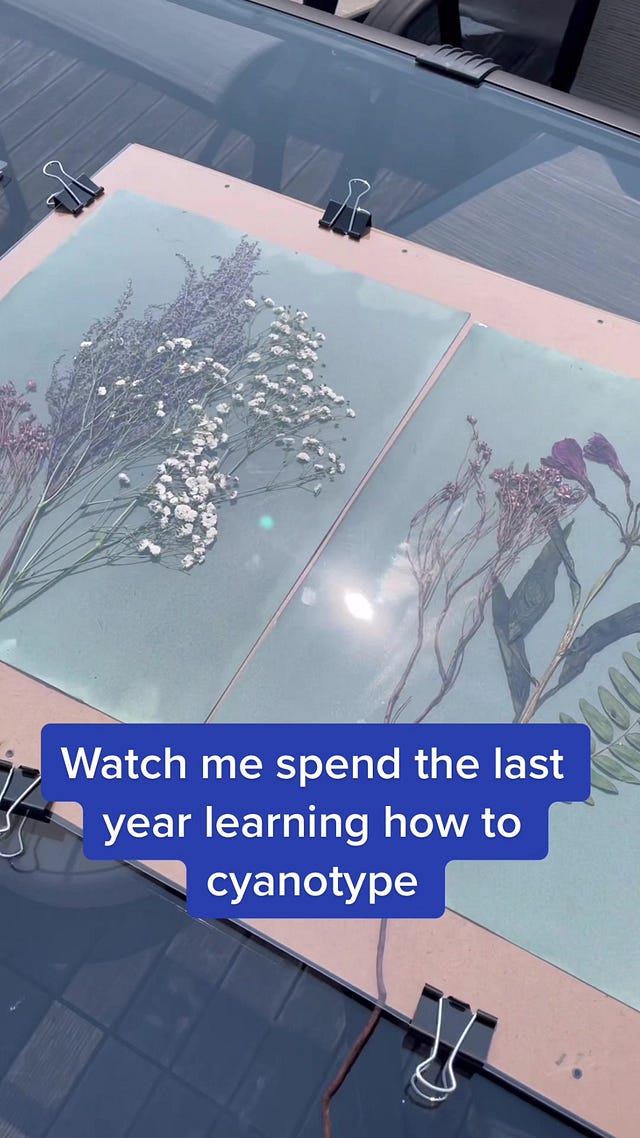

Growing up in a digital world with no solid walls where the images are always disappearing could accurately be described as some kind of horror, so it makes a lot of sense to me that Gen Z is turning back to bygone image-making processes like cyanotyping, and buying so much 35mm film they brought Kodak back from the dead.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The choice to go analog in a digital world is not really about the finished product. The process is the appeal — it’s a kind of meditation. The repetition of filling and shading, the full-body sigh when your hand finishes a curved line. All the failure before the sweet joy of getting it right. The solidity of being able to touch an art object, instead of just having to believe it exists somewhere as data on a server.

Of course, dead art processes are seeing a resurgence partly because their Real Time is being compressed into easily consumable short-form. You can go analog all you want, but will anyone see what you’ve made if you don’t perform speed for the void? I ask because I don’t have answers; because although I know how digital feeds warp my experience of time, I still can’t find a way to live without them.

Lately when I put down my phone, I find myself reaching for a pen. Reading a book is hard — the mind wanders — but the steady pressure of drawing a line brings me back to Real Time. The slowness is the point; it puts me back together.

I watch some artists, as well, but I watch the real time ones, while I'm also working on my own. It's like hanging out and making things side by side with a friend.

I resonate with this so much! Except time lapse of plants growing or absorbing water are still super satisfying for me, bc there’s nothing for me to compare myself to. It’s just plants being planty!