The Real Difference Between Adderall and Meth

part 1: on "medication stigma" and the fear of addiction

I took mixed amphetamine salts the other weekend, on a 20-hour drive from Florida to Philly. I was given this drug when I got diagnosed with ADHD as a teenager in the late aughts, but stopped filling my prescriptions after a while, mostly because I disliked how stimulants made me feel: tunnel-visioned and vaguely agitated. But the first time I take one after a long hiatus, I have to admit, it feels good.

The boring interstate I’d traversed a hundred times suddenly opened up to me, and my mind unfurled into an elaborate, excited idea. I became totally engrossed in conversation with my partner — my words, which so easily get stuck, flowed effortlessly out of my mouth. It was both a pleasurable treat and a useful tool, and it got me through a slog of a drive that I always deeply dread.

This mix of amphetamine salts, which you probably know as Adderall, is currently in shortage, causing all kinds of problems for people with prescriptions who rely on it everyday. And, predictably, the discourse has been abuzz about why we’re running low, with many pointing to overprescribing by shady telehealth companies that capitalized on “drug-seekers” who don’t “really have” ADHD during the pandemic.

There have been comparisons to the opioid epidemic, too. A WIRED headline claims “America’s Adderall Shortage Could Kill People”, expressing fear that patients could be forced into the illicit drug market for their medicine and accidentally buy meth instead.

Chemically, these two are almost twins. But Adderall is medicine, many argue, and comparing it to meth is deeply offensive. Adderall is respectable, because it’s prescribed by a doctor — it’s not just something you want to take for pleasure, it’s something you need.

So I started wondering: who deserves this drug, and who doesn’t? How did amphetamine become a hallowed medicine, and methamphetamine an evil poison? And what does prohibition have to do with all of it?

Creating the The Medicine-Drug Divide

The popular YouTube channel How To ADHD begins a video on medication stigma like this:

“There is an intense stigma against stimulant medication… In the media and on social media we are bombarded with misleading and shame-inducing messages.”

The video cuts immediately to a clip of Dr. Carl Hart, a neuroscientist and pharmacology researcher, in a 2014 interview with MSNBC’s Chris Hayes. The exchange goes:

DR. HART: When we think about methamphetamine, think about Adderall, Adderall is the attention deficit disorder drug that a lot of college students take, same drug, nobody’s talking about—

HAYES: [interrupting] It’s not the same drug.

DR. HART: It’s the exact same drug.

They insert a shot of Hayes' face looking skeptical (which was not in the original edit), before jumping into more examples of ways that people compare Adderall to street drugs. These editing choices portray Hart as a fear-mongering talking head that wants to take your medicine away from you, but being a fan of his work, I knew that was a gross mischaracterization.

Dr. Hart, a Black man who grew up in a poor neighborhood in Miami, published a book in 2021 called Drug Use for Grown-Ups, in which he openly discusses his recreational drug use. He argues that most of what we think we know about the dangers of drugs is just racist, classist propaganda, and the real danger is the way prohibition laws mandate widespread ignorance about the drugs we take and how they work.

The drug panic du jour fentanyl, for instance, is used safely in hospitals every single day, because medical professionals have access to information about dosage that the layperson does not. Likewise, the danger of accidentally buying meth on the street instead of Adderall is not the methamphetamine1 itself, but the fact that you have no idea what you’re taking.

It’s strange to see Dr. Hart appear as an enemy in a video about drug stigma, because fighting it is actually his life’s work. Agitated by this misrepresentation, I looked up the rest of the clip that How To ADHD cut short. Hart continues:

“The only difference is that methamphetamine has a methyl group attached to it, but we did a study in which we…tested the effects of a drug like Adderall compared to methamphetamine. They produced identical effects. They are almost identical chemically, in terms of the chemical structure. They’re the same effects, but we have these wildly different narratives.”

These narratives are what he believes we need to confront if we want to tackle stigma and make drugs safer for everyone, not just those who can access a prescription for them.

Breaking down the constructed barrier between medicine and drug, deserving patient and non-deserving user, is central to Hart’s mission. But How To ADHD apparently disagrees with this strategy, instead choosing to reinforce the divide.

What they’re calling “medication stigma” about stimulants is actually just drug stigma in general, but the problem for How to ADHD is not that drugs have been stigmatized for political reasons — it’s that this stigma is sticking a little too hard to a drug they want to see as medicine.

In the video, they show some responses they received when they asked ADHD Twitter for personal experiences with medication stigma, saying:

“One person’s mom avoided getting her diagnosed at all because they didn’t want her to become an addict.”

This fear of becoming “an addict” did not come out of nowhere — there’s over a century of state propaganda behind it in the US. Addiction has become an American boogeyman because we were scared straight into thinking that illicit drugs have some magical power to ruin our lives after “just one hit.”

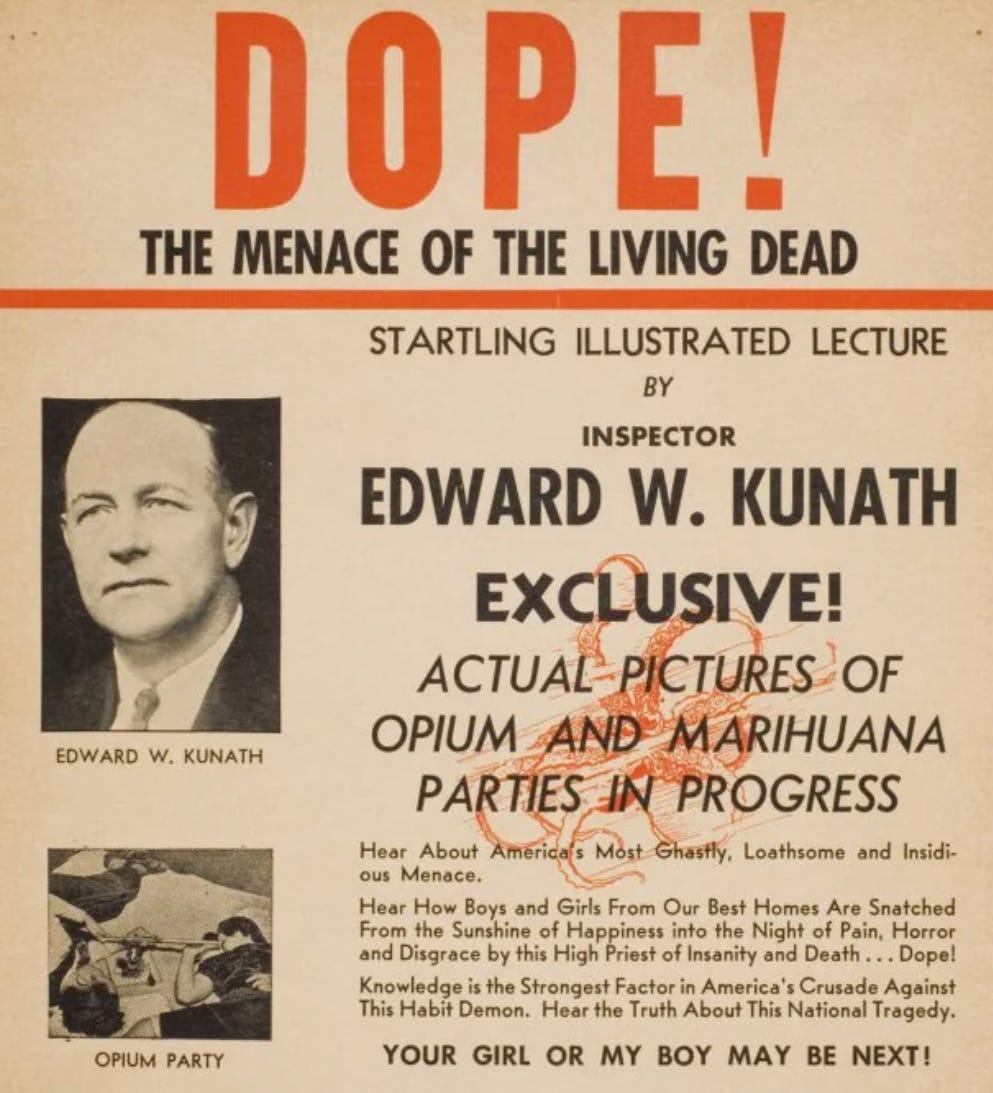

Take this copy from a 1930’s propaganda poster:

“Hear How Boys and Girls From Our Best Homes Are Snatched From the Sunshine of Happiness into the Night of Pain, Horror, and Disgrace by this High Priest of Insanity and Death…Dope!”

Okay?? The drama! Except, that isn’t how addiction works. Compulsive habits develop over time through what neuroscientist Marc Lewis calls “motivated repetition,” and a person is motivated to repeat drug use for complex social and psychological reasons, often things like poverty, isolation, and trauma.

Much popular discourse about Adderall centers on easing the fear of addiction by insisting that “when taken as prescribed,” there is no risk. But all drugs have both benefits and risks, and all drugs can be used in both helpful and harmful ways. The difference here is not the drug, it’s the supervision by authority.

In his recent book, drug historian David Herzberg explains how the medicine-drug divide was constructed, largely by doctors in the early 20th century who saw an opportunity to expand their power. This created what he calls a “white market” for substances:

“For over a century, providing sedatives, stimulants, and opioids to patients has been one of the single most common therapeutic acts in American medical and pharmacy practice. This has been so consistently true, for so long, that it cannot be written off as an accident or aberration; it has been a primary function of the medical system. The driving question in American drug history has not been how to prohibit use of addictive drugs, but how to define the medical—that is, how to determine who should have access to drugs, under what circumstances.” [emphasis mine]

Herzberg explains that in the later half of the 1800’s, rapid industrialization led to widespread use of opium and cocaine by “white, native born, Protestant, middle aged, and middle class” people, who he calls the “doctor-visiting classes”. People who could not afford to see a doctor also used drugs, they just got them through more informal channels, often in urban “vice districts” where immigrants and people of color were segregated.

Rapid industrialization meant lots of products became more easily accessible with few safety guidelines, and this led to a public health crisis that affected all kinds of products. When it came to drugs, Herzberg explains, officials saw the medical market and the vice market as distinct issues:

“Opium smoking and other informal-market drug use attracted the attention and zeal of moral crusaders and anti-immigrant activists, who incorporated addiction into their broader campaign to govern urban vices, especially by policing white women’s sexuality. Morphine and other medical-market drugs, on the other hand, were tackled by a slowly emerging coalition of consumer advocates and therapeutic reformers who saw addiction as one more example of the need to protect the public by regulating commerce. Together, these two campaigns built the legal and cultural architecture of the medicine-drug divide.”

While both groups were essentially using the same chemicals, white morphine users were seen as deserving, because they suffered from “neurasthenia” due to the unique pressures of being so educated and civilized (seriously, that is what the newspapers said back then), while Chinese opium users were referred to as evil and undeserving, getting high in sinister “dens” that lured white women into debauchery.2

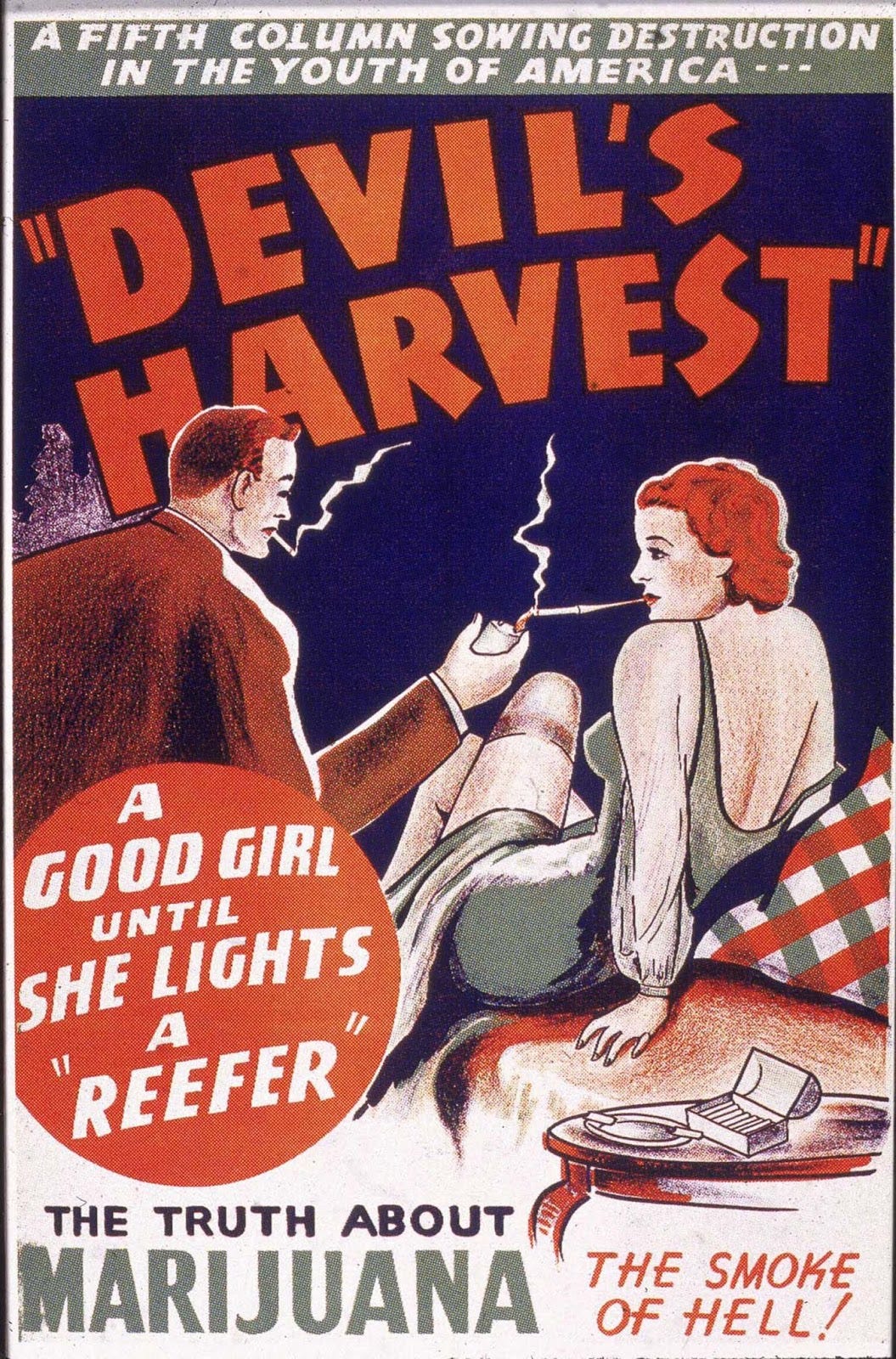

This is the same racist argument that would be made in the decades following about cannabis — white women were assumed innocent and used as pawns3 in a crusade against Mexican immigrants, who were accused of bringing “marijuana” into the US, and Black musicians, who were targeted for smoking it in jazz clubs.

These are political constructions based in race and class, and they are still with us today. Journalists are using the term "modern opium den" in headlines to scare people about safe injection sites. Turn on Fox News and you’ll see plenty of handwringing over “Mexican drug cartels” luring your (innocent, white) kids with colorful fentanyl candies — despite the fact that the War on Drugs created the prohibition market for those drug cartels in the first place.4

I see this legacy, albeit a bit more subtly, in the insistence that Adderall is completely different from meth. The difference is not so much chemical as it is contextual — Adderall the medicine for the doctor-visiting classes, meth the poison on the street.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been both an ADHD patient and a recreational drug user, but I just can’t get behind any stigma-fighting strategy that off-loads my stigma onto another vulnerable group of people instead. When asked what we can really do to address stigma in society, anthropologist Roy Richard Grinker had this to say:

“I think there are two things that I find important for us to do. One of them is to recognize what the real source of the persistence of stigma is. It’s not lack of education, it’s not ignorance, it’s not lack of awareness. The source of the persistence of stigma is whatever our ideal person is at a particular point in time. What is stigmatized is that which is not considered good. So what we are starting to do is change that perception of what is good and useful…we need to challenge those as devalued, and say that we value these different ways of being. That is what will reduce stigma.”

fun fact: meth is actually approved as a treatment for ADHD under the brand name Desoxyn

A great book about this in particular is Ilana Mountains’ Cultural Ecstasies: Drugs, Gender, and the Social Imaginary. It wasn’t just white women’s sexuality — weed was also blamed for making people gay and trans. At an American Psychiatric Association meeting in 1934, it was said that cannabis “releases inhibitions and restraints imposed by society and allows individuals to act out their drives openly [and] act as sexual stimulant [particularly to] overt homosexuals.”

If you are still like, okay but why are they so colorful, though?? Two anonymous Sinaloa cartel members recently told Insider they're actually tinting the fentanyl as a safety precaution to make it harder for drug dealers to mix it into other white powders like cocaine.

I just saw something today demonizing ketamine the same way, basically saying that ketamine for depression is a bad thing because if people have access they will misuse it (no discussion of the proportion of people who might benefit/stay alive from better access and lower cost).

Ahhh this is exactly the article I needed. I feel like I keep having this conversation with people. Like it’s just /not/ that different. Thank you for always somehow reading my mind and producing such quality content to put words to my random thoughts.

Also, bonus! The button to switch from free subscriber to paid subscriber finally works properly! Been trying to do that for a while. Woo hoo!