You Are A Body

on trying to understand yourself with a camera

You are a body, I think, as I float weightless in cyan, tracking whispy clouds. A pair of ibis glide overhead toward their sunset roost. I feel most like a body in water — free of gravity’s ceaseless pull. You are a body, I think, as I kick with both feet to the bottom. It’s easy to forget, when you spend so much time in your head.

I am learning how to pull myself back when I start to float away from my skin. When it peels from my bones like old yellow wallpaper and spiders begin their weaving, I knock at the doorframe of my body and pull the curtains back. Hello, I am in here. I can’t be anywhere else. I have to try to reckon with it, renovate and nest.

You are a body that maybe you don’t like. One you can’t look at in the mirror. You are a body that gets old, gets frail, becomes unable. You are a body that hurts, a body that can’t do the things it did last year, or yesterday. But you are a body, regardless. So how do you live with that?

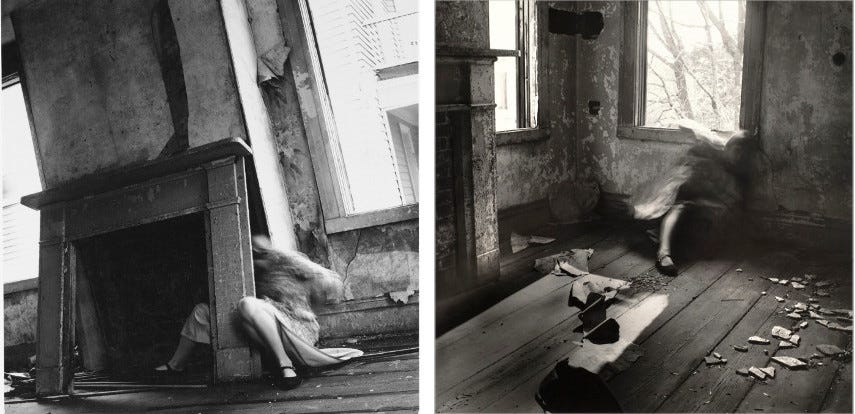

While studying art in college, I went through a nude self-portrait phase. At the time I thought it was just a practical decision — models are hard to schedule and direct. I knew what I wanted the shots to look like, so it was easier to just pose for them myself. The artist Francesca Woodman, famous for her eerie self-portraits, called photographing herself “a matter of convenience”, too.

But now I look back and think: I was trying to reckon with being a body.

I remember looking at the images with a strange sort of detachment. I didn’t feel shame. It was fine for other people to see this naked body, because it was just a body. It wasn’t me. I hung that body up in a museum, submitted it as a thesis. But every time I uncurled from my pose and stomped around to the back of the camera to see what I’d gotten, I was surprised at what I saw. I was pinning myself to a board like a dead bug, marveling.

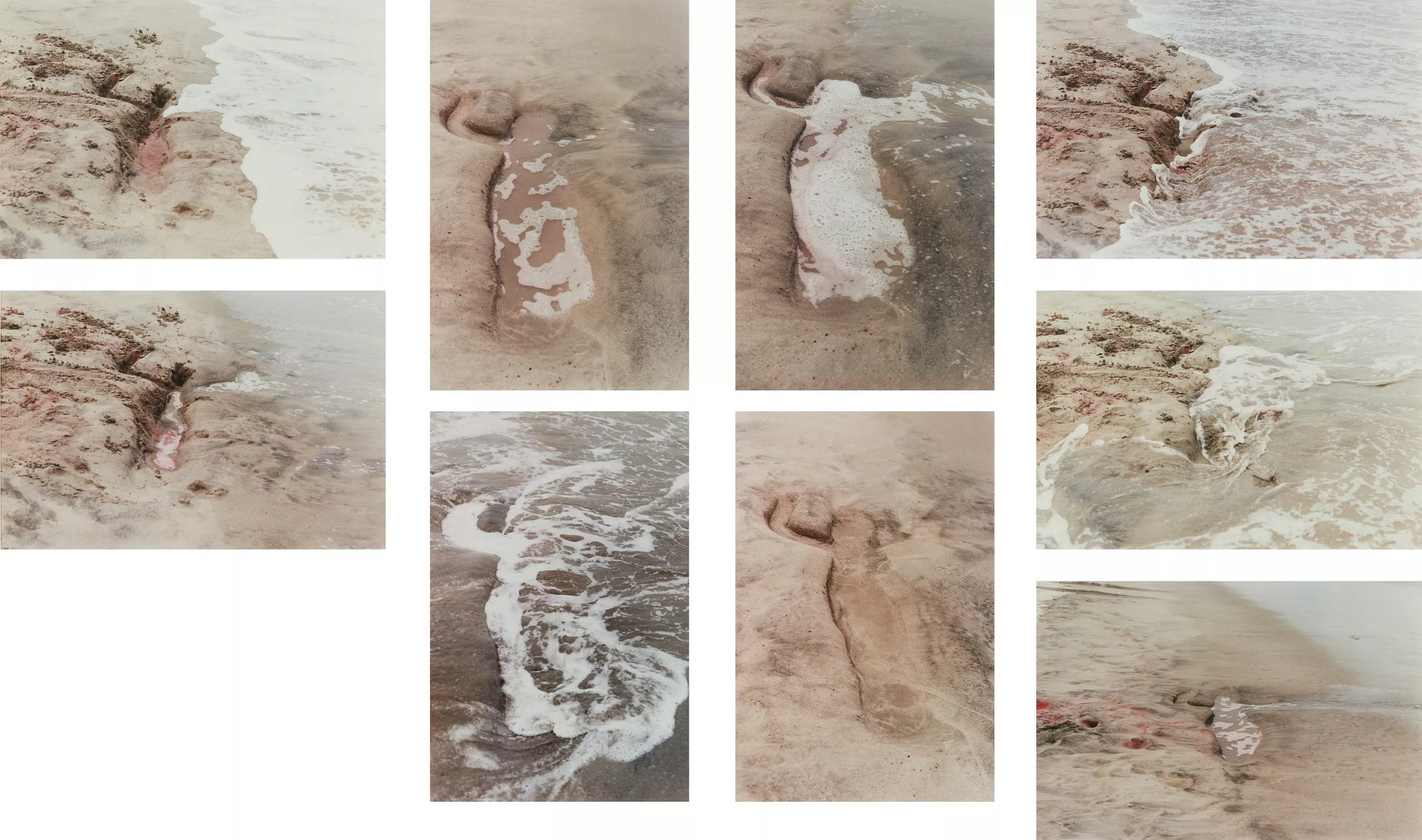

Artists have been using the camera to grapple with their bodies for a long time. The late performance artist Ana Mendieta is most famous for a series of images documenting the imprint of her body in the landscape. They are ephemeral, transformed by the elements, until eventually the lines of her silhouette merge with the earth.

Sent to Iowa from Cuba at the age of 14, she was grappling with a profound sense of displacement. Mendieta didn’t want to see her body as separate, but as belonging somewhere, as part of something bigger.

Her sister, Raquel, described the evolution she saw of Mendieta’s work, which began with paintings of what she hoped would become an “icon that inspires worship”:

During those seven years Ana's works evolved from performance pieces—in which her silhouette was left on the ground—to actual carvings of female figures on the earth. In 1978, she said of her art, "I work with the earth, I make sculptures in the landscape. Because I have no motherland, I feel a need to join with the earth, to return to her womb." And return she did, over and over again…until Ana became the earth and the earth goddess became Ana.

The beauty of good art is that everyone sees something personal in it. Writer Jennifer Brough, who has fibromyalgia, explained in Artsy that the way Mendieta’s work addressed “the shifting nature of identity” helped her come to terms with the fluctuations of her chronic pain:

The shifting nature of pain in fibromyalgia means that it is both present and absent—two states coexisting in the same body.

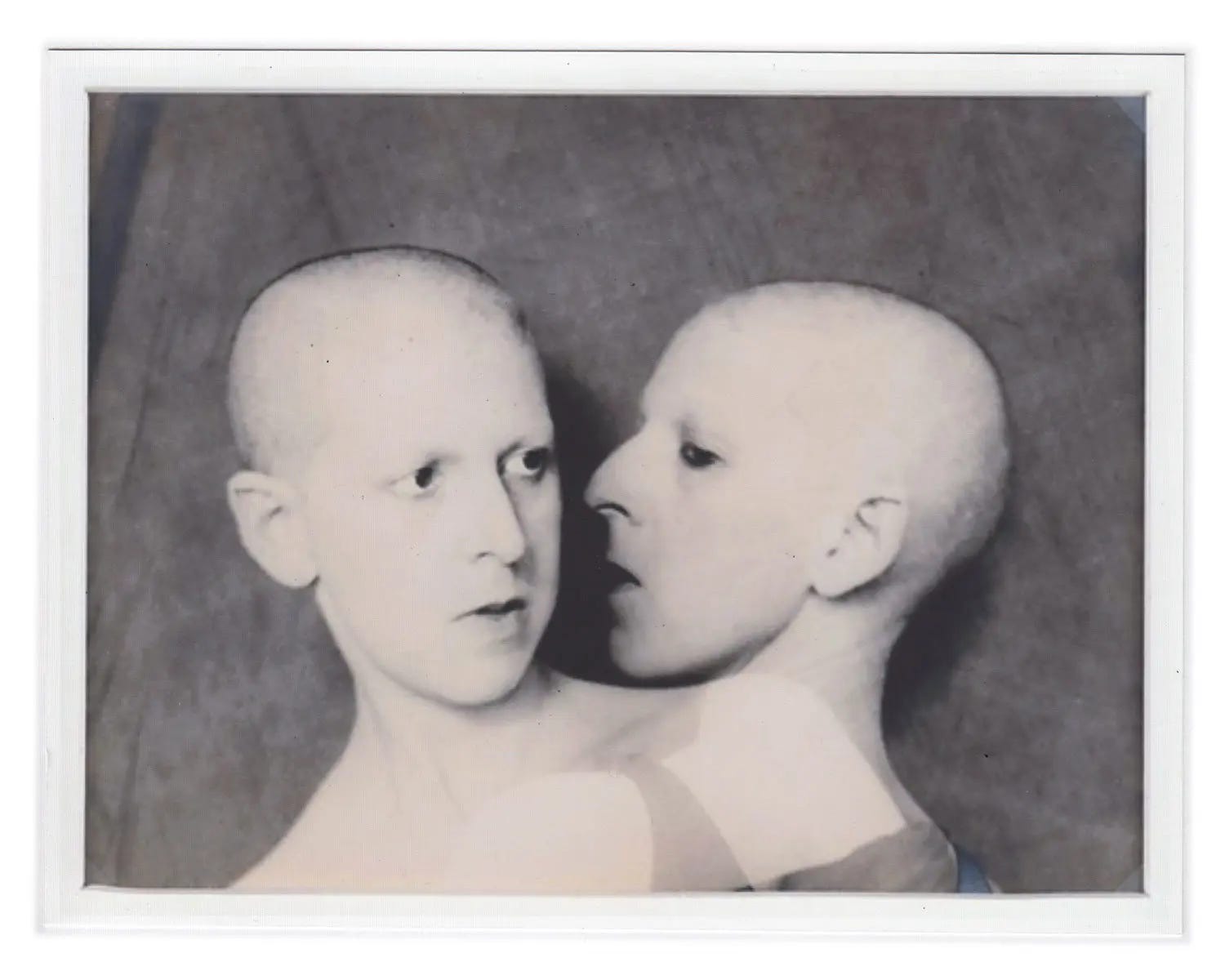

The body can contain multitudes. The non-binary French artist Claude Cahun used a camera to explore coexisting states in the body more than 50 years before Judith Butler theorized the performativity of gender. In their book Disavowels, Cahun wrote:

Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.

The serial nature of photography makes it well-suited to explore multiplicity. In one of the most famous, The Kitchen Table Series, Carrie Mae Weems set up a camera in her kitchen to document the many roles she embodied as a Black woman in America. The framing never changes, just the scenes within it, creating a narrative of Weems’ life, even though we never see anything but her kitchen table.

Weems has said:

I am both subject and object; performer and director.

Her figure guides us into story, like Mendieta’s silhouette leads us into the woods, like the self-portrait takes us by the hand and shows us versions of ourselves.

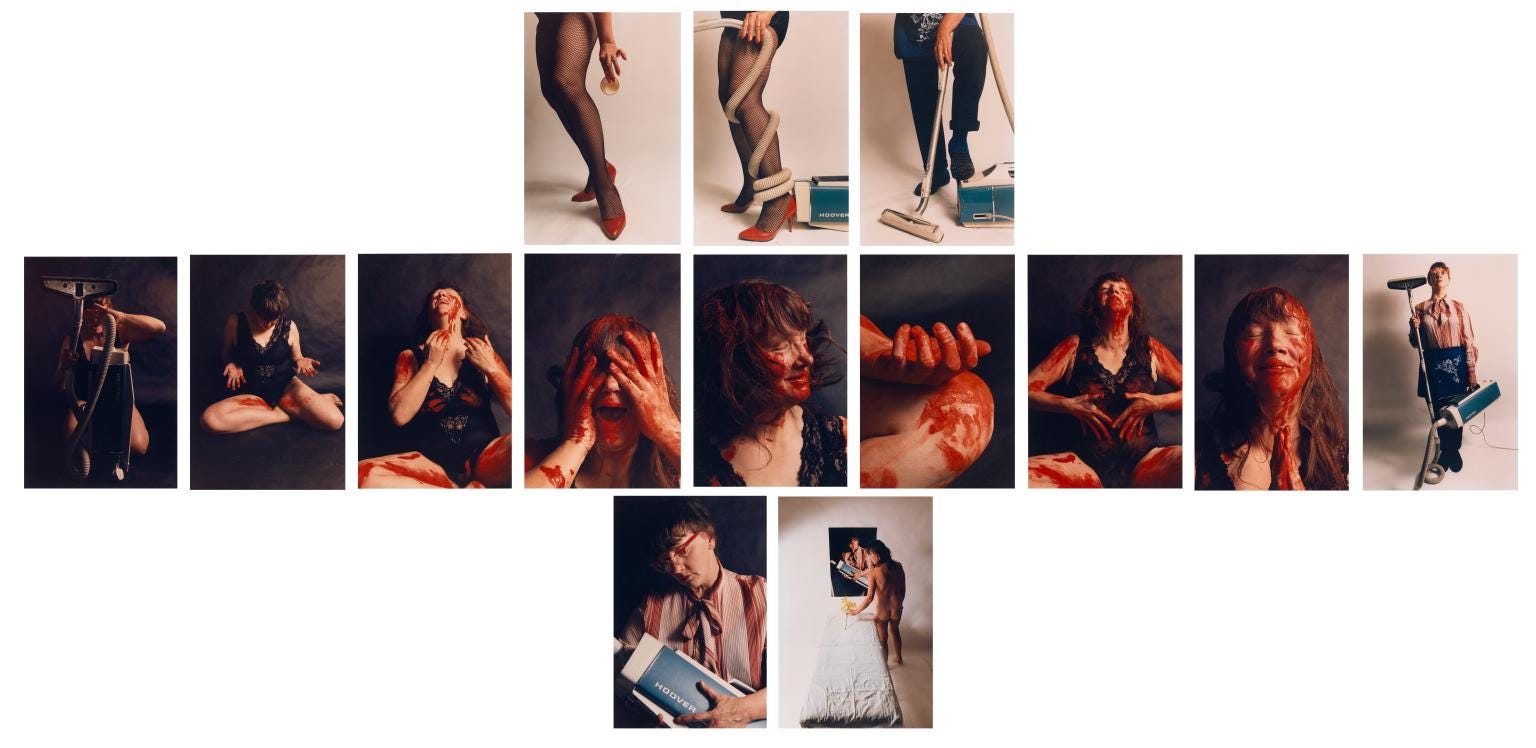

Or at least, that’s how the photographer Jo Spence used it. The camera helped her understand her body when she became ill, making images of herself even on her death bed. In collaboration with Rosy Martin, she created Photo Therapy, a process that uses re-enactment to sort through experiences and feelings that are difficult to verbalize.

Martin told Elephant:

…this work contests the idea of any possible idealised image of the self, since that is an impossibility anyway. Rather, it embraces and attempts to make visible the multiplicity of identities that any individual inhabits throughout their lives.

Maybe I was doing photo therapy, back then. Maybe I was grounding myself in my shifting bones with every mirror shot. You are a body, see? Photographing the self isn’t vanity — it’s a proclamation. Like a handprint in a cave saying, I’m here.

I haven’t photographed myself in years. A camera can help you ground or float, depending. The still image captures — it takes all the transformation and flux and shifting of my body and fixes it in place, permanent. I used to need that, to freeze the moments flying past me so I could look at them longer. It was a way to process from a safe distance, to be an observer in my own life.

For a long time I wouldn’t leave the house without my camera. Even if I didn’t take it out of my bag, just knowing it was there if I needed it was enough. It was a tool, a brush, a crutch. A weight I had to carry. I could put it between me and the world and feel safe. I could point it at my body and locate myself in space.

But I can’t look at an image of my body and tell you how it feels. It’s just light and geometry, a false promise of fixity. The truth is, the body’s condition is change.

Here is a version of me eight years ago, falling in love too fast with a stranger on a houseboat in Amsterdam. He’d gone to work, and I’d photographed my body in the fading afternoon light. I look at this image and see a ghost now, just a revenant that haunts the minds of people who knew her. I became someone else.

To be a body is to transform. The cells in your blood, the bacteria in your gut, the molecules in your head — they never stop changing. Even decay is generative, feeding soil. We can keep trying to fix ourselves in place with a machine that freezes light, but photographs are just flat snapshots in the dynamic flow of time.

Why do we fear transformation when when we’ve never known anything else? You are a body, and you will have many bodies. The challenge is learning how to change with them.

Extended Footnotes

Tangents I discovered while gathering materials for this piece that did not fit into this essay but I need to tell you about anyway include: Claude Cahun’s anti-fascist art activism, the posthumous myth-making around Francesca Woodman, and a neuroscientist talking about the illusion of a singular self. But first, some context.