Who's Afraid of Fake Dopamine?

dopamine dispatch #3: you're already a cyborg! plus -> the very American mythology of the influencer-entrepreneur

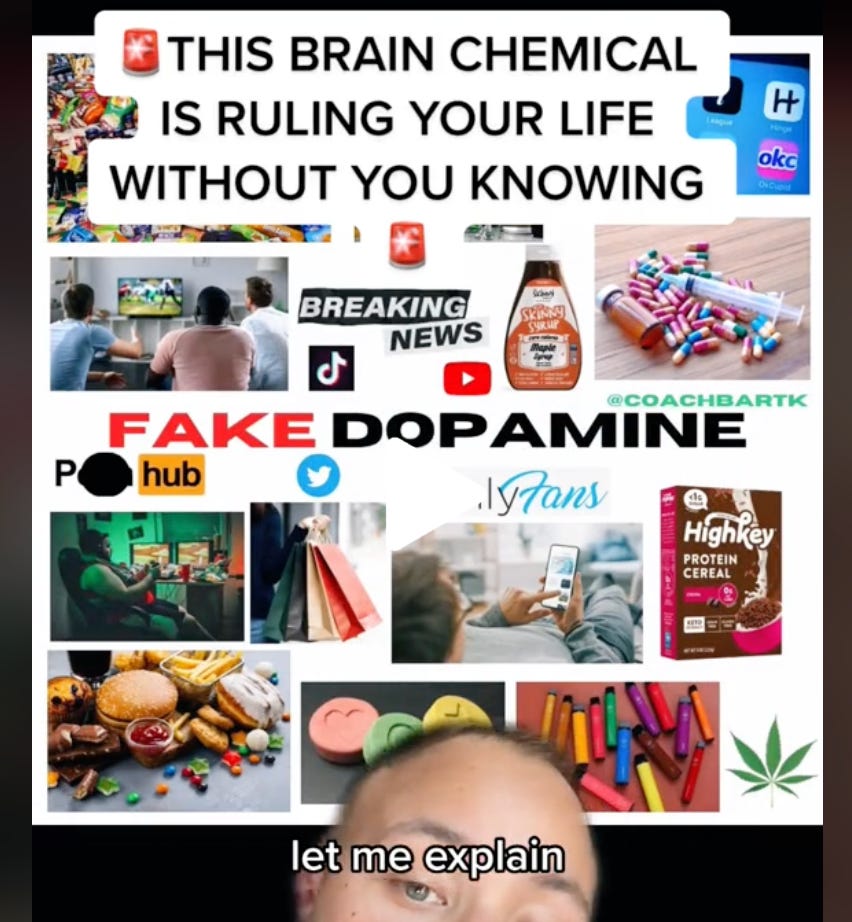

I’ve noticed an idea spreading on social media that goes like this: real dopamine comes from things like the sun, exercise, and a good night’s sleep. Dopamine from porn, drugs, video games, and social media? That’s fake dopamine. It’s artificial, which means it’s bad for you, so cut it out!!!

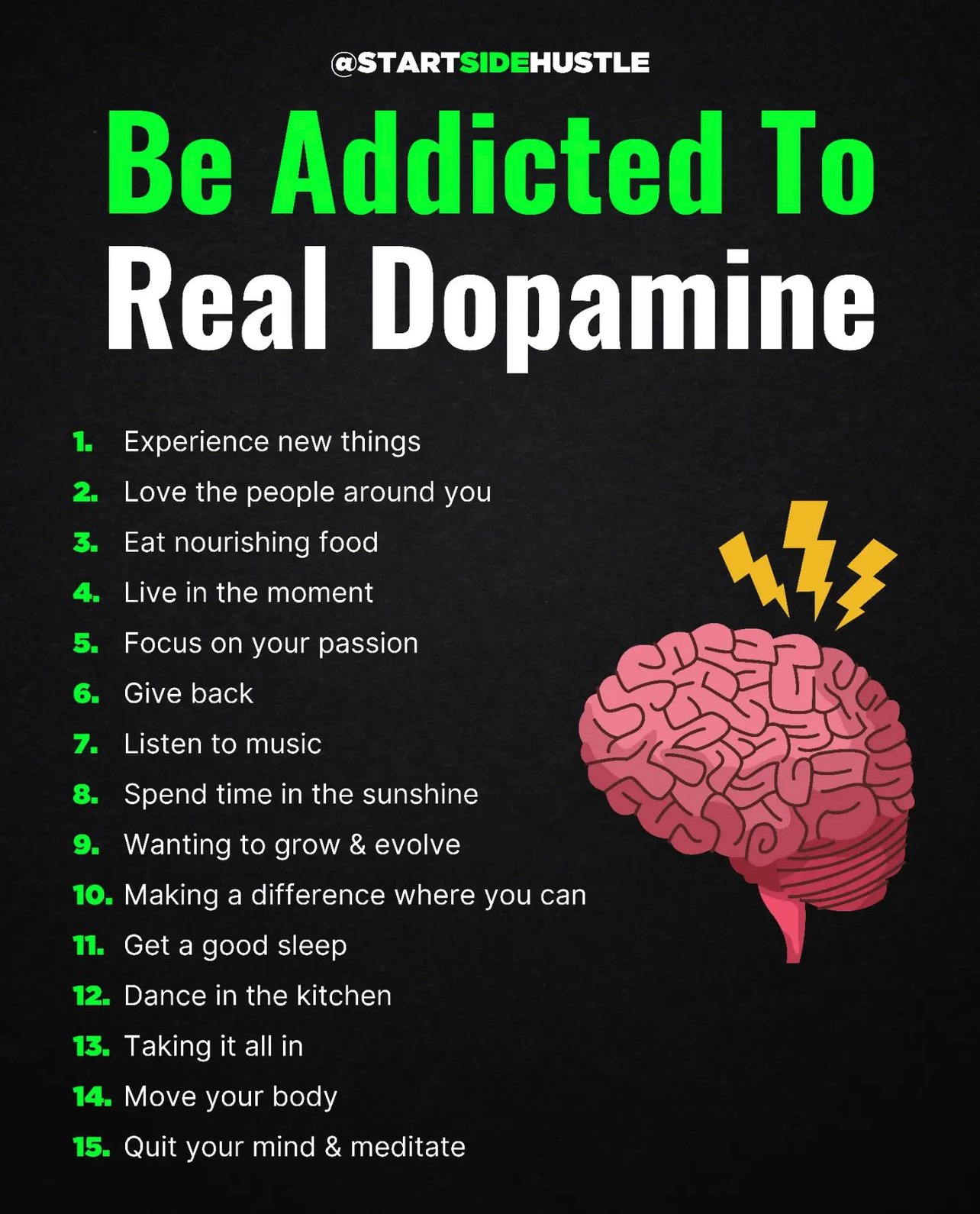

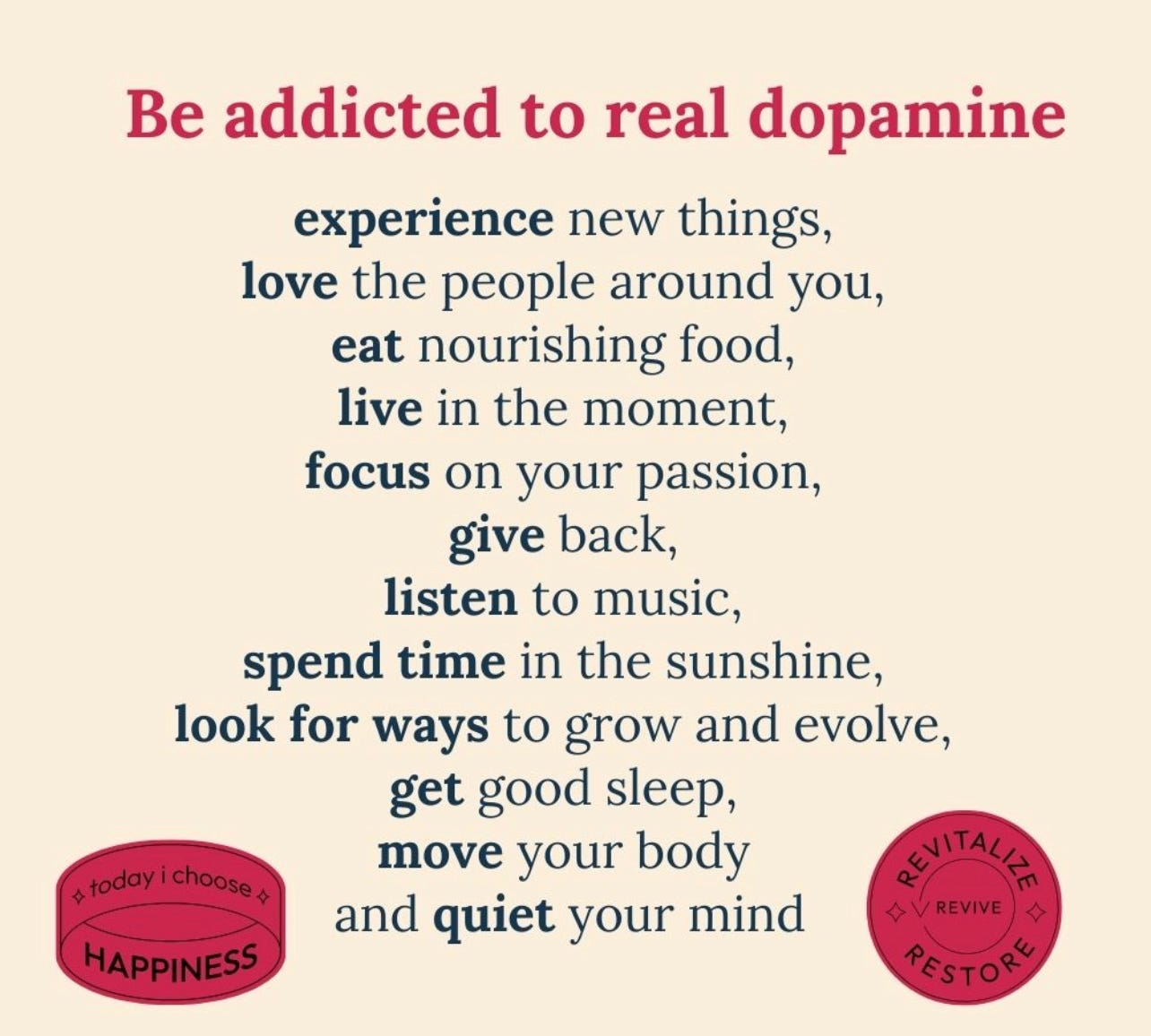

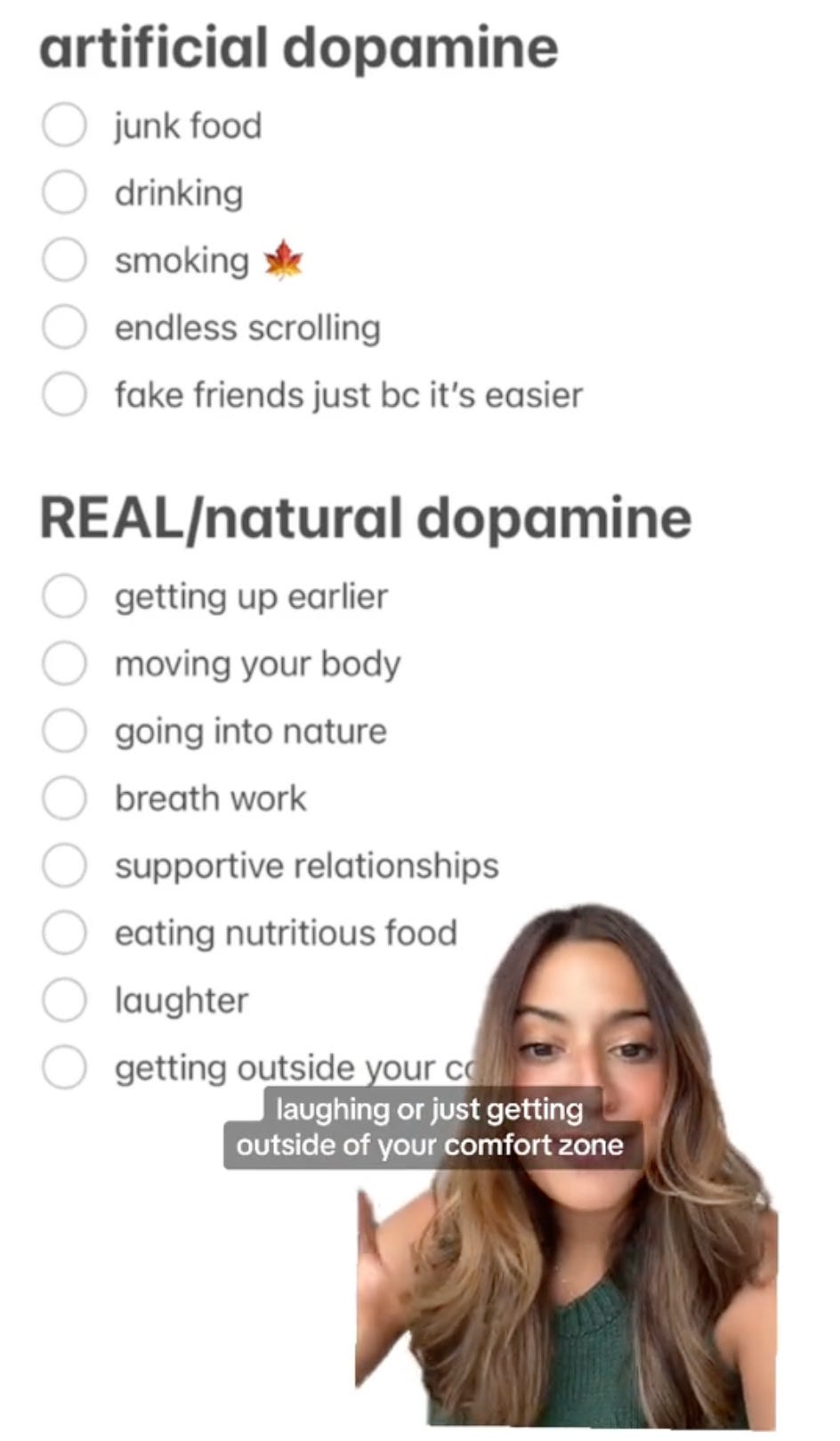

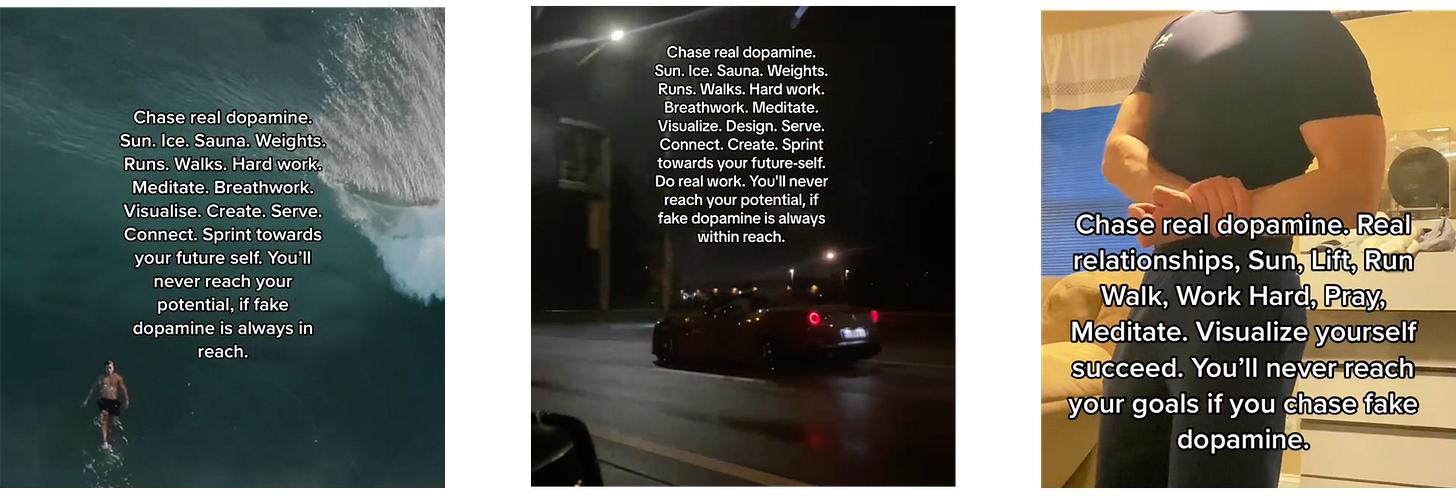

This idea is, ironically, expressed through a litany of soulless infographics that look suspiciously like they were created by AI:

But the real/fake dopamine binary has also spread to TikTok, where people post versions of the same text on top of videos of themselves staring into the camera serenely or lifting weights at the gym. “As a society, we most often tend to reach for artificial dopamine,” one lifestyle influencer says in a TikTok. “Why? Because it’s easier and faster.” Learning to tap into real, or “natural” dopamine, has been great for her health, she says, but it’s “really uncomfortable at first,” because you have to do work to get it.

In truth, the only thing that could maybe be called “fake” dopamine is the Parkinson’s drug L-DOPA (although it’s technically a dopamine pre-cursor, chemists don’t come for me). That doesn’t matter, though, because the dopamine mythos isn’t really a scientific claim. It’s a linguistic sleight-of-hand — using a science word to mask a moral claim. I think there’s actually a deeper anxiety about artificiality going on here, one that rhymes with wellness culture’s enduring fear of toxins.

Eula Biss likens toxin anxiety to an older fear of filth — both of which have triggered an obsession with controlling the body. It’s a losing game, though — Biss writes that “we are all already polluted,” our bodies “continuous with everything here on earth,” and I would argue that technology is no exception.

In her book The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age (such a sick title), Sandy Stone writes about going to see a talk by Stephen Hawking. She was outside the room, listening to his voice come over a PA system, and wanted to get closer so she could “actually hear Hawking give the talk.” Stone snuck in and made it into the first row, where she realized, standing in front of Hawking, that his voice was no different — it was computerized either way.

Observing that he and his speech device had merged to make his person, she asks: “Where are his edges?”

Stone, who is considered the founder of trans studies, has spent her life exploring this question about the edges between technology and the body. It’s a thread shared by much work in critical disability studies, which looks at how disability complicates the notion of a “natural” or “normal” human body. It seems absurd to fear the artificial when you live with a pacemaker installed in your chest or take synthetic hormones for your health everyday — something, by the way, cis people do all the time, and yet, many still haven’t quite accepted what Stone’s mentor Donna Haraway wrote in 1985 about us all being cyborgs now.

Stone refers to objects of tech — like a radio, a recording console, and Hawking’s speech device — as prostheses. “An extension of my will, my instrumentality,” she writes, “That’s a prosthesis, all right.”

“It’s not that machines are taking over,” cyborg anthropologist Amber Case said in a 2012 TED Talk, “It’s that they’re helping us to be more human.” For Case, our smartphone-prosthesis is a “technosocial wormhole” that allows us to reach across time and space to connect to each other. It’s an extension of our brains that holds our memories, social connections, and identities. Does that make us all artificial, or is it just a different way of being real?

The dopamine mythos and its mechanistic view of behavior tend to flatten a lot of humanity. People don’t scroll social media and play video games simply as a form of “easier and faster” pleasure-seeking — we do it to have an experience in a virtual world. The controller and the keyboard are prostheses for interaction. “Inside the little box are other people,” Stone writes.

Take video games, for example — popular games are both realistic and social. Kids use games to try out different social roles, to relax or escape, and to express themselves; adults use games to stay connected to family and even to remember deceased loved ones, interacting with the digital “ghosts” they left behind in saved video games. Tech can mean more than just a cheap thrill, but Stone says that much theorizing about human-computer interaction is based on the Calvinist idea that work toward a goal is what defines being human. She thinks this idea overlooks the importance of play, “purposive activities that do not appear to be directly goal oriented.”

Echoing the Calvinist principle that work defines the human being, these memes only consider dopamine “real” if it comes from activities that contribute to achieving goals. Health has become synonymous with hard work, and pleasure is not a viable end in itself, but rather, a path to self-destruction.

In an essay called What Is Health and How Do You Get It?, Richard Klein rejects this definition of health and asks us to think about what it might mean if we took a page out of Epicurean philosophy, which views pleasure as a necessity:

Not only is health the sine qua non of pleasure (that without which there is none), but pleasure improves your health. Put another way, if you inhibit the body’s pleasure, you provoke disease.

For Klein, pleasure denial is not only unhealthy, it doesn’t even work! Citing Klein, scholar Deborah Lupton notes “the contradiction of repression as incitement” — prohibition makes things even more pleasurable. “Attraction + obstacle = excitement” wrote sex therapist Jack Morin, and this principle, dubbed the erotic equation, holds true for more than just sex. Lupton writes:

"Health promotional imperatives, thus, may be conceptualized as an integral dimension of the 'dark pleasures' of the behaviours they prohibit, serving to intensify their enjoyment by rendering them sins."

Maybe the path to true moderation, then, is not abstinence, but facing the fear of our sin. We must find the beauty in our filth, our toxicity, our fake (micro)plastic cyborg bodies. In the words of Julian K. Jarboe:

“Why does God create grapes and wheat, but not wine and bread? God does this because God wants us to share in the act of creation. To be how you made me, to become how God made me, through you, I can remake myself. You and I: we are already only whole, and shifting towards the divine.”

For paid subscribers this week:

Where did this iteration of the fake dopamine meme come from? And what does the influencer-entrepreneur have to do with Laura Ingalls Wilder, Walden Pond, and America’s favorite myth?