The Psychology of Not Evacuating

PLUS: Made-Up Machine Time, Another Reason Social Media Makes Us Feel Like Shit, and Why The US Military Is Taking the Trip Out of Psychedelics

Hello slugs,

This newsletter is going to be a bit of a bummer, I’m sorry. (And if you have natural disaster trauma, be trigger warned.) I’m going to leave the first section outside the paywall because I want everyone to be able to read it.

Last week was horrific for me, watching my hometown get devastated by Hurricane Ian on the news from 1,000 miles away, losing touch with my family during the worst of it on Wednesday afternoon and not being able to sleep.

I finally got to talk to my parents Thursday night, and thankfully everyone is safe. Their house sits outside the flood zone, but they didn’t have time to board up the windows — in a serious stroke of luck, the only thing damaged was their trees. (A beloved 30-foot loblolly pine in the backyard, home to a red-tailed hawk, snapped in half.)

Some of my other family members had flooding, roof damage, and lost vehicles to the storm surge, but considering the apocalyptic images coming out of Fort Myers Beach, that’s honestly a relief.

My dad, who’s weathered hurricanes in Southwest Florida for over 40 years, told me that the storm left him speechless — I have never seen anything like it, either. It was an extreme weather event, rapid intensification fueled by warm ocean water, the likes of which I fear will only continue in frequency.

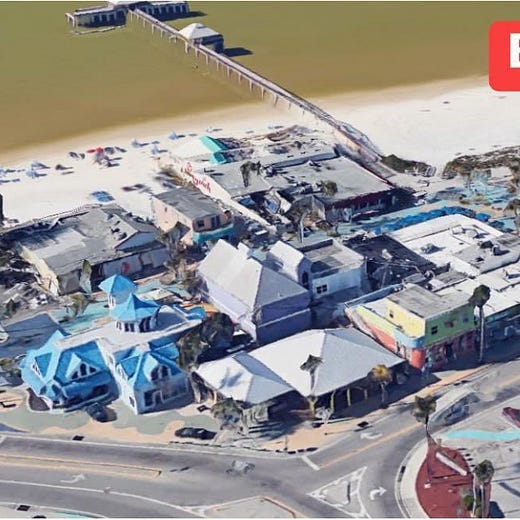

I feel immense grief and I don’t know what to do with it. My brain can’t fathom that these places I grew up in, full of so much history, have just been wiped off the map. Seeing the first aerial shots of the pier reduced to pilings was a punch in the stomach.

I spent every Monday evening doing man-on-the-street interviews on that pier when I edited the local Fort Myers Beach newspaper — my first story was on renovations to the town’s Times Square, the area around the pier that got leveled last week.

Working at the paper, I went to every town council meeting and got deeply familiar with all the local drama, the small businesses, the town characters, and the ecological issues, and I can tell you, that town of 5,600 people basically had its heart ripped out.

Times Square was the island’s center of hospitality, Southwest Florida’s main industry and a major source of income for working class people across the region. Fort Myers Beach and Sanibel were the top tourist destinations in the county.

The only bridge to Sanibel collapsed in multiple places. Hundreds of service industry workers lost their livelihoods overnight. Historic buildings and homes washed away into the ocean; beloved community members died. Search and rescue efforts are ongoing (over 60 people confirmed dead so far), and horrifying stories continue to surface.

One survivor told the Miami Herald:

“Everyone on this island is going to need a lot of therapy,” he said. “We rescued an old couple who had to tread water for hours. We pulled them out of a flooded laundromat where they said they were holding onto whatever they could to keep afloat.”

I had to go on Twitter to keep up with the news about Ian, which meant I was also bombarded with gross opportunistic blue-check political discourse and heartless users debating whether we should care about people who were told to evacuate and did not. It’s a question that makes my stomach turn to even consider.

Of course we should care — it doesn’t matter why someone stayed, or if they had the means to leave and chose not to. But the question of why people stay seems to mystify the media every time a major hurricane rolls through. There are a lot of reasons, like money and disability, that people find acceptable.

A lot of people stay home because they know how hard it is to get back afterward, with road closures and gas scarce, and there is a real danger of losing your job if you can’t make it back quickly. (Many of my family members are already back to work — my aunt, an ER nurse, went back in soon after the storm passed.)

But then there are less tangible reasons that people stay, which often gets chalked up to “stupidity”. I bristle whenever someone describes another person’s decision as stupid just because they don’t understand it. People make choices for reasons, and what’s truly ignorant is not trying to understand them.

The Washington Post covered the stories of people who chose not to evacuate before Ian hit, and one person they interviewed said:

“The way they make it seem on the news — you know 10, 15 feet — I’ve never seen that,” he said. “Even when it was predicted in the past.”

That 15 feet of storm surge did happen, and it shocked a lot of born-and-raised Floridians — people like my mom, who was an infant when Hurricane Donna ripped my grandmother’s roof off and forced them to flee to a neighbor’s house as the eye passed over. And me, who played outside in the eye of Hurricane Andrew at two years old.

When you grow up on the Gulf Coast, hurricanes can feel like a thing that’s in your blood. There is a real false alarm effect that happens — you get used to the storms, and you get used to the media sensationalizing them, and you figure it won’t be that bad, because all the last times weren’t that bad. You board up and hunker down with your loved ones and you ride it out. But things are changing, storms are growing worse with warming oceans, and our past experiences are no longer so reliable.

The perception that people who choose to stay are either stupid or lazy is a common one and, according to a study conducted after Hurricane Katrina, inaccurate. A team of researchers looked at the mismatch between public perception and survivor experience — from the outside, people who stayed were similarly denigrated.

But that wasn’t how survivors talked about their experiences:

“The people who stayed, on the other hand, experienced their actions very differently,” Stephens continues. “They didn’t just sit there and do nothing, as they were perceived. They didn’t just wait around for the hurricane to destroy them. They did the best that they could given the situations that they were in. People worked together with other people. They cared for their families and communities. They tried to maintain strength and resilience. They had different ways of responding—they did what they could with what they had available to them.”

These accusations of laziness and negligence are ultimately rooted in America’s bootstrap mentality:

Survivors who evacuated consistently spoke of independence, choice, and control. Those who stayed emphasized their interdependence with others, their strength in the face of adversity, and their faith in God.

“The perspective of the observers was much more consistent with the people who evacuated,” Stephens says, in part because both groups belonged almost entirely to the American middle class. Observers and those who evacuated both shared notions of independence and control—common elements of the independent model of agency that permeates mainstream American culture.

The tendency to look down on people who did not evacuate comes out of the belief that it’s possible to escape storms if you just make the right choices — literally, but figuratively, too. Calling survivors stupid or lazy is a way of saying, “That would never happen to me.”

But even when you do make all the “right” choices and evacuate, it’s not uncommon for a storm to turn and hit you anyway, a story I’ve heard many times in Florida over the years. Victim-blaming can provide an observer the illusion of control in the face of horror — nothing scares people more than the truth that we are tiny and powerless to the sublime forces of nature.

Fort Myers Beach is a very small town with a very strong sense of community, and while the choice to stay on the island may be absolutely mystifying to many people, I understand why a lot of people did, and why many are still refusing to leave despite being told that getting the power and water fixed could take months to years.

The connection to your home and your community is not necessarily a logical one — it’s “a feeling that can’t be quantified,” as the Washington Post put it. People make decisions based on these kinds of feelings, too. That’s not stupidity, it’s just human.

I feel nothing but compassion for everyone who stayed, no matter the reason. If you value autonomy and agency, you must also uphold the dignity of risk — the right to make mistakes — and the belief that people still deserve care and support when they do.

No one deserves the natural disasters that happen to them. I’m left with an ocean of sadness, grief, and fear, because I know these storms will only get worse, and these disasters will keep coming. I know that my family will never leave Florida, and the Gulf Coast will continue to have a front row seat at the tragedies of climate change.

I don’t know how to end this but to say, if you want to be angry at anyone, be angry at the billionaires who have sold the planet down the river for personal wealth. Be angry at politicians who have been paid to do nothing much about it. (And no, not just the Republicans.) Be angry that vulnerable coastal communities of people and animals alike are being considered a necessary sacrifice to the god of unending economic growth. And grieve — do not neglect to grieve.

I Deleted Instagram Again

I found myself doomscrolling at 4AM this week and going on angry IG story rants, behaviors which I’ve begun to take as signals that it is time to delete the app for a while. My friend Naomi (a memer I met on IG who recently deleted her account), sent me this quote by culture critic Neil Postman, and I felt like it was a fucking big mood: