Nathan Fielder’s Masking Opus

The Rehearsal is a work of autistic culture, whether he embraces it or not

I’ll admit it, I never watched Nathan For You. The Rehearsal was my first introduction to Nathan Fielder’s comedy, and five minutes in, I clocked it as very autistic.

So did a lot of autistic people online:

Fielder’s work has been called autistic since Nathan For You, and he’s denied any association (despite also admitting that he took inspiration from autistic people). But you can’t blame autistics for relating to him when he says things like this:

Sometimes, in the earlier things I was doing, when it would go in front of an audience, I would wonder why people laughed at a certain thing because I didn’t see it as a joke, I just saw that as how I was acting. But through doing a lot of that, I think I’ve gotten better.

Or stuff like this:

“Well, I hate talking about myself,” he said. He claimed this had something to do with a lifelong struggle to articulate his thoughts. When he was in elementary school, a speech therapist told him he knew fewer than 500 words, which bothered him so much his mother gave him a book of advanced words like abreast. (“Not ‘a breast,’ ” he clarified.) “I still, to this day, feel like I don’t know a lot of words. Maybe it’s that.”

And also this:

At 13, he transferred to a large public school, a bewildering experience. “I didn’t understand how people made friends,” he said. Performing magic, he soon discovered, was easier than conjuring small talk. “You’re saying, ‘Here’s what we’re going to engage about.’ And then when the trick is done, the interaction ends,” he said with a laugh.

The New Yorker described his new show as “a self-portrait of a man trying to reach past his relentless solipsism”, which, interestingly, was something a New Yorker critic also said about Hannah Gadsby’s comedy special Douglas (a great example of autistic humor) — her “solipsism masquerades as art”.

Media critic Sarah Kurchak responded:

For autistic people, that’s a familiar critique: Our sincerity is often found lacking by outside observers, and we’re often accused of self-absorption.

When I say Fielder’s work is very autistic, I don’t mean it in a diagnostic sense. I mean that his work is culturally autistic, whether Fielder is or not. This is an idea I discovered in the book Autistic Disturbances by Julia Miele Rodas. In the foreword, Remi Yergeau writes:

Rodas masterfully makes the case that autism is an art, one that publics are beholden to recognize and value.

The problem is that most people don’t recognize the autistic qualities in their favorite art, because most people think of autism as a disorder, not a culture. Rodas seeks to change this by looking at several famous works of literature through the lens of “autism poetics”, of which she identifies 6 characteristics: silence, ricochet, apostrophe, ejaculation, discretion, and invention.

Silence is a hallmark of Fielder’s comedy — he embraces the awkwardness and comedic effect of long silences, which most other shows would edit out. Jimmy Kimmel has praised his use of silence in Nathan For You:

“The silence is maybe the best part of the show. There are moments where he and the person he’s interviewing are just kind of looking at each other. I love that.”

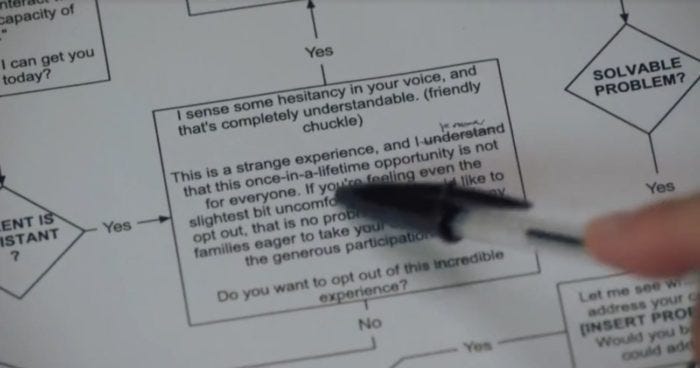

Discretion, the impulse to order and taxonomize, is Nathan’s entire approach to social situations on The Rehearsal. See: the flow charts he uses to predict where conversations will go for his participants, and the scene where he uses one to make a series of phone calls to the parents of child actors who are auditioning for the show.

Ricochet, or repetition, is pushed over the edge for laughs, with Nathan often repeating a scenario over and over again in increasingly bizarre ways. In an extreme perspective-taking experiment, he embodies one of his students’ lives, even moving into his apartment, in order to figure out how the student sees him as a teacher.

In the season finale, after he makes a mistake that emotionally harms a child, he runs a past scenario multiple times with different child actors to figure out if there was something he could have done better. Repetition pushed to the point of absurdity is a large part of the show’s jokes.

Ejaculation, or sudden disruption, is also central to Fielder’s comedic approach. Going back to that old interview I posted above, he explains where this comes from:

My mum has like a way of kind of being very like um, smooth in conversation, like she’s very good at talking with people, so I think when I was younger I always tried to throw her a curve ball that would make her feel uncomfortable and throw her off her guard, but also try and make her laugh, because I feel like then kind of, your true personality comes out when you kind of have to deal with something you don’t really expect.

You could consider Fielder deeply in denial about the autistic-ness of his work, or you could argue that it’s an offensive appropriation of sorts. Kurchak described it as:

Personally, I have conflicting feelings. Do I find the show funny? Yes. Is it ethically questionable? Also yes (although you could argue that’s true for the entire genre of reality TV). By rejecting associations with autism, is Fielder laughing at us, and not with us? Maybe, but in Episode 5, he insists that “No one is the joke” — it’s the social dynamics that he’s fascinated by, the uncomfortable scenarios that are funny to him. (Something else that, I’m sorry, is just very autistic.)

The show makes some poignant insights about the human condition — the issue, really, is that autistic people are often excluded from that condition, while other people relate to and celebrate art that is culturally autistic. But autistic experiences are human experiences, too, and once you start looking, you can see them everywhere in pop culture and art.

In Autistic Disturbances, Rodas asks:

Is it ever truly possible to say entirely what we mean or to mean entirely what we say? Does language, used by anyone in any form, exist as a fully intentional medium, transparently communicative, a direct expressive conduit of some true inner self?

Or, are we all just performing versions of ourselves for each other?

The Rehearsal is interested in these questions, too. Some of us, like Nathan, may recognize the performativity inherent in socializing, and some of us may need to rehearse our performances more — we call this “masking”. But just because you don’t see your performance or consciously practice it, doesn’t mean you’re not doing it.

The Rehearsal is funny and relatable because, as Fielder points out, social awkwardness is a pretty universal experience, and joking about it is something most people can find catharsis in. Masking, too, isn’t something only autistic people do — it’s just something we’re more willing to be honest about.

This piece brought back a lot of conflicting feelings I remember squirming around in while watching Nathan for You and the first 2 episodes of The Rehearsal. Been meaning to get back to Unmasking Autism by Dr. Devon Price - I'm even more curious how the book and The Rehearsal will land with the connections you've written about in the back of my mind.

How To with John Wilson (which Nathan Fielder is an executive producer on) is another show that I found really affecting, also more wholesome, that feels similarly culturally autistic.

Thanks for added layer of nuance to view these through!

I hope you're receiving a new audience with the new season out. I've enjoyed your writing. It felt very generous and fair, but most importantly, it validated my own feelings and suspicious ;)

Nathan (and even if it's just the character that he chooses to share with the world) is such a beautiful representation of autistic people.

Remember some of the hokey, one-dimensional portrayals of gay men back then? They were the comedic relief with flamboyant fashion, lisp, caustic humor and too much thirst.

That is kinda where we were with someone like Sheldon and Nathan is a welcome evolution.