Everything That Flows Makes Fractals

On ketamine, neuritogenesis, and the surprisingly beautiful science of ego death

I think I know what it might be like to die, thanks to 80mg of ketamine.

The philosopher Raphaël Millière came up with a cheeky acronym for what is possibly the most intense experience you can have of your own consciousness without actually leaving this mortal plane: DIED, or, Drug-Induced Ego Dissolution. According to Millière, DIED happens when a drug disrupts the brain's ability to integrate a range of sensory information into a coherent model of a ‘self’ that is separate from the world.

I wasn’t ready when I DIED. I was cocky, and disrespectful. I’d snorted enough ketamine in nightclub bathrooms that I assumed we were well-acquainted already, but a heroic dose injected is a different beast.

It started as a sense of space expanding. I felt like I was lying on the floor of a huge room, a room where the ceiling went up and up forever until it turned into night sky.1 Eventually the space expanded so far that it began to collapse back in on itself, spiraling in and exploding out all at once.

The void branched and twisted, fractals on fractals. There was no more me; I forgot myself. I had no memories, no sense of being anywhere at all.

Leaving ‘I’ behind like this is a cosmic horror, but because ketamine is a strong sedative, I couldn’t physically feel afraid. This is a mercy — the drug took me to the edge of nothingness, while keeping me from feeling the terror of it. Right before my entire being collapsed, I thought: you have to remember what this is like so you can describe it later.

Joke’s on the part of me that describes, I guess, because there was nothing left to observe and categorize. Ego death is ‘beyond words, beyond space-time, beyond self’, as Timothy Leary wrote in The Psychedelic Experience.

I spent most of the next day trying to fathom what had happened, to find words to talk about it, but it was like trying to remember a dream, where the only part you can hold on to is the feeling.

Some of the best descriptions of the ketamine experience come from the yoga teacher and past-life regression practitioner Marcia Moore, who documented her explorations of what she called ‘the bright world’ with her anesthesiologist husband in the late 70’s.2

She wrote that ketamine was like ‘a mill wheel’ that ‘entirely rubbed out’ her ‘small personal concerns,’ an ‘infinite washing machine’ in which she was ‘tumbling round and round,’ ‘caught up, turned inside out, and sucked impulsively into the revolving maw.’

“Even though the memory of that state remains it can only be called ‘indescribable’. To speak of a thunderous silence, or a multidimensional sphere turning upon itself, or of identification with undifferentiated vibratory energy is probably as close as words can come to portraying a truly ineffable condition of existence. This inner realm, full of sound, color, and sensation was itself entirely formless. Here there could be no distinctions between subject and object, this and that, I and thou. Only the vast nameless faceless process remained, churning on and on and on.”

Consistent in these descriptions is a sense of movement — churning, tumbling, spinning, revolving. That is one thing I do remember vividly from my own experience; it felt like being inside a swirling tunnel, expanding and contracting all at once. This “tunnel trip” is common, according to the expert Karl Jansen, who describes ketamine as ‘one of the most split drugs ever discovered’:

“It both wakes people up and puts them to sleep. It over-excites the calm brain and calms the over-excited brain. Ketamine is both damaging and protective, pro-and anti-convulsant, addictive and a treatment for addiction. It is given during birth and to ease the passage into death..”

Jansen likens ketamine trips to near-death experiences, in which people also report experiencing a dissociative, swirling tunnel journey. But what is up with the tunnel? Why do so many of us see it?

Maybe it’s another dimension, or what happens when consciousness breaks free from the body — that would be cool. I want to believe! Unfortunately, I also found a more boring, mathematical explanation.

In a 2002 paper titled What Geometric Visual Hallucinations Tell Us about the Visual Cortex, Bressloff and colleagues argue that drugs destabilize the visual cortex, which could lead to horizontal lines in the tissue getting mapped into concentric circles when the brain translates them into vision, where vertical lines could get mapped as radiating, like spokes on a wheel. Combined, this would create the illusion of depth — a tunnel.3

And what about the fractals? When I came back from the void, I couldn’t stop thinking about them. I started reading about how scientists think ketamine works in the brain, and found the theory of neuritogenesis.

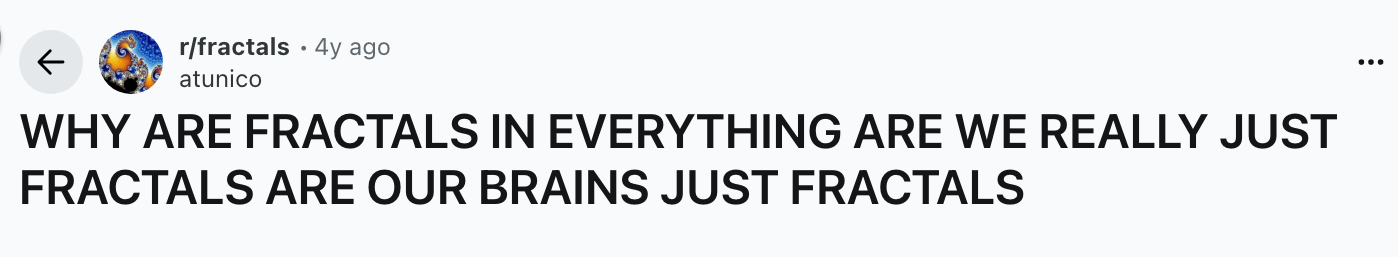

Research starting in 2018 found that ketamine, along with other psychedelics like LSD, DMT, and psilocybin, ‘increased dendritic arbor complexity’ — they stimulated neurons to sprout new branches. Or, you could say: they made fractals.

This inspired a new term for these kinds of drugs: psychoplastogen, which etymologically means, mind-molding agent. There’s some debate in the field over whether the effects of psychoplastogens are biologically independent of the trip — can they stimulate neuritogenesis on a strictly biochemical level, or is the mystical experience is necessary?

So far I am in the latter camp — I’m not sure you can separate the drug from the experience, although some are trying. Psychedelic researchers have criticized psychiatry for trying to isolate the chemistry from its social context:

“The simplified mainstream narratives ignore broader knowledge and perspectives about psychedelic use and mechanism of action. The seemingly controversial argument that psychedelics’ therapeutic efficacy is dependent on suggestibility, social context, and cultural priors challenges traditional psychopharmacological views. But for anyone who seeks universal scientific truths about psychedelics, these might be their principal mechanism of action, a non-specific amplification of context,4 which is strongly-related to sociality, especially interpersonal relations and cultural setting.”

In other words, psychedelics are context-dependent, social tools, and trying to individualize them through mail-order service and market-based healthcare models may be denying the very thing that makes them effective — their sociality.5

While its become a 21st-century mental health craze (and certainly some people are being professionally swindled), Jansen calls the use of altered states ‘probably the oldest technique in medicine, dating from the period when the roles of priest and doctor were united in one person.’

“The practice was so ubiquitous in the ancient world that it should effectively be considered a species ‘norm’,” Daniel R George and colleagues argue.

“What is unusual is the active suppression of such substances, a late twentieth century global phenomenon led by the United States and United Nations (albeit with deeper roots in Christianity and the colonial Americas).”

Which brings up a good question from the researcher David B. Yaden:

“..if you can provide an experience that many people report as being the most meaningful of their entire lives, is it unethical to withhold it from them?”

The story of ketamine’s biology focuses on glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter that has become quite popular in recent years. “Like the shy kid who suddenly became visible with a new haircut, glutamate has taken the neuroscience literature by storm,” Mia Michaela Pal writes.

Dr. John Krystal, head of psychiatry at Yale and a leading ketamine researcher, analogizes ketamine’s mechanism of action to ‘if you had a brake and then you had another brake that you stepped on to relieve the brake’6 — it inhibits the inhibitor, GABA, which triggers the release of excitatory glutamate, leading to a wide range of downstream effects, like neuritogenesis.7

This is called the ‘disinhibition hypothesis,’ and it marks a departure from the chemical imbalance theory of depression. It’s not about correcting a ‘balance’ of neurotransmitters, but using a drug to intervene on their action in a way that helps the brain change.

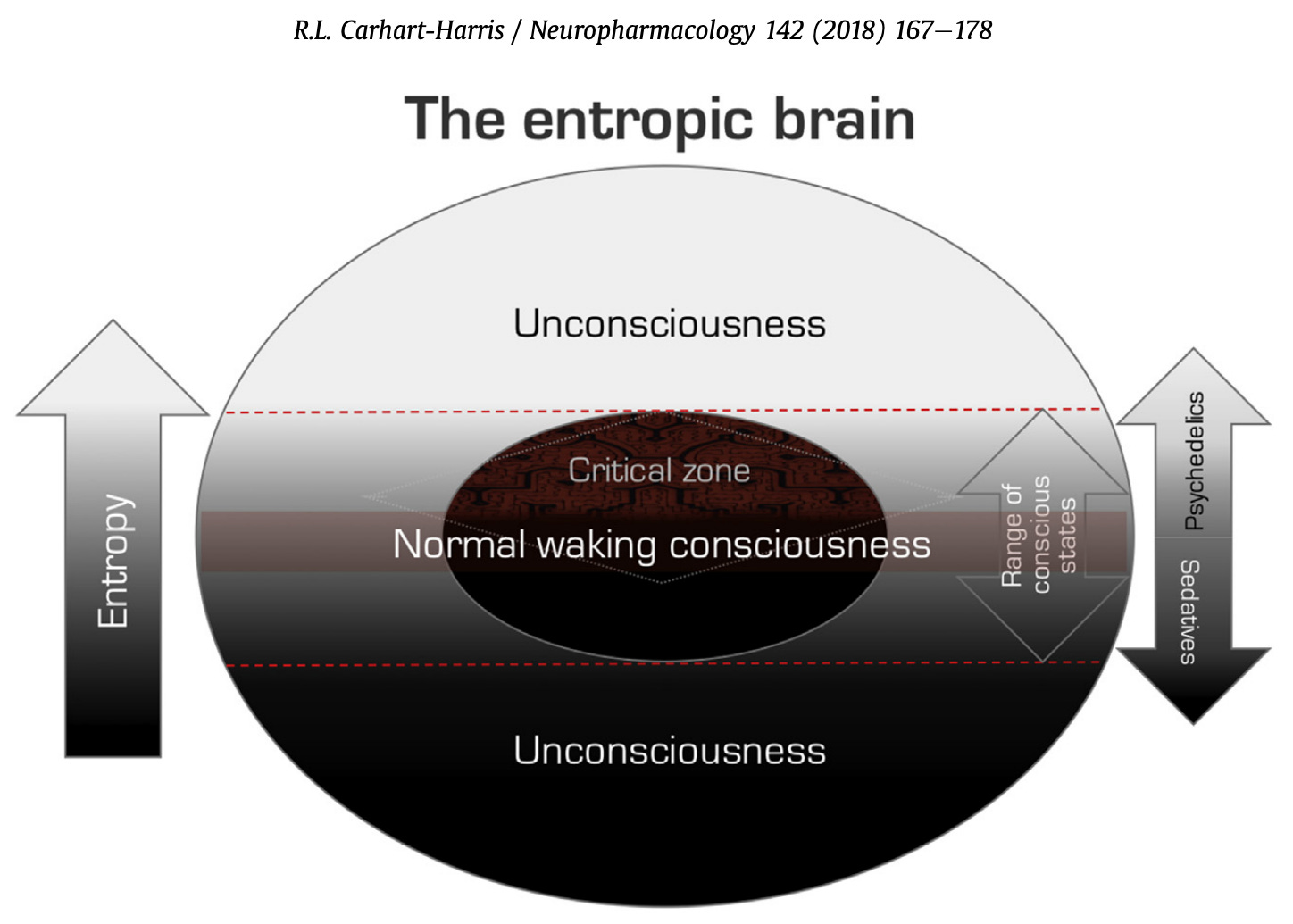

Biological mechanisms aside, another way of thinking about how psychoplastogens work is that disorder, for a moment, can be therapeutic. The psychopharmacologist Robin Carhart-Harris says they shift the brain into an “anarchic” state that is “highly entropic,” or more random.

If we think of depression and anxiety as pathologically stuck states, then this could be a ‘useful kind of scrambling up’, as Carhartt-Harris says:

“I’ve likened it to shaking a snow globe where, you know, the snow might get settled in a particular way, but once we shake it up, we can change things.”8

Central to this idea is the theory of the brain as a prediction engine.9 Rather than responding to experiences, this theory says that the brain is constantly making predictions about what we see in front of us for efficiency’s sake.

Depression could be seen as a negative prediction, a sort of neurological doomerism — things are bad, they will always be bad, and there is no hope. A psychedelic trip could disrupt this prediction for a moment, creating a window for change.

In Granta, the writer Sheila Heti describes her own experience of this window after two sessions of ketamine therapy. The drug removed the filter of social convention that she usually puts on herself, allowing her to actually be honest with a therapist about her fears of rejection. She worries to him that she is ‘dimming’ her partner, but also has the epiphany that relationships brighten, too.

In the days after her session, other possibilities became available to her:

“..in little ways, which are always big ways, I felt myself acting and thinking differently. For one thing, silence from other people didn’t seem like punishment. Unreturned emails felt like nothing. And I really paid attention to brightening, not dimming, Jack. Maybe I could wash his car? I thought, imagining other ways I might help him, for he was always, in practical ways, helping me. And so I did wash his car, and it was even fun. And he seemed happier, too.”

A participant in the 2021 ‘Ketamine and me’ project says something similar:

“I could see a future, I could see that I was capable of doing things…I didn't kind of feel the sort of the negative person sitting on your shoulder telling you that you can't do this there's a problem here…. It was almost as if…the angel and the demon on your shoulder, and all you could hear was the angel.”

A friend of mine is fond of saying that ketamine puts you ‘two steps away from the bitch in your head,’ which can be a huge relief when the bitch in your head gets way too loud. For me, being able to momentarily disconnect from my psych-ache is immensely therapeutic — dissociation allows me to directly experience that another existence is possible.10

However it works, ketamine reminds me that the neurons in my brain are shaped like the trees outside my window and the watershed around my house. It is fractals all the way up, to the level of galaxy and universe. Wherever something flows — water, oxygen, electricity — you will find a fractal system, rhizomatic.11

“Everything must flow,” Marcia Moore concluded after one of her trips. “This was to be lesson number one.”

“Oceanic boundlessness” is the technical term.

Moore mysteriously disappeared in the winter of 1979, shortly after the book she wrote with her husband, Journeys Into the Bright World, was published, and her remains were found two years later in the woods near her house. I went down a massive rabbit hole about this where I spent like three hours reading a true crime book and ended up editing her wikipedia page in a fit of righteous indignation. I stumbled across this story in a paper by Edward Domino, who did the first human experiment with ketamine, and whose wife invented the term “dissociative anesthetic” for it. Domino uses Moore as a cautionary tale, implying that she did too much ketamine, wandered into the woods, and froze to death (which is also what her wikipedia page said.) He wrote that “her husband warned her of its dangers”!!! But according to a 2021 book by Joseph and Marina DiSomma, her husband admitted to a subsequent girlfriend that he had killed her with ketamine and dumped her body in the woods. She said he bragged about how easy it was to trick the police, and seemed proud of all the news coverage of him and the case. She also described him as abusive and said he forcibly injected her with drugs; his ex-wife told the DiSommas that she thought he hated women. When Jansen interviewed him for the book Ketamine: Dreams and Realities (which I also cite here), Alltounian told him she had killed herself with ketamine, and again she is used as a cautionary tale. Jansen presents her husband as a victim of Moore’s wild personality and penchant for drugs, which is just so fucking misogynistic I can’t even deal!!!! He killed her!!!! (Allegedly! But he’s also dead now so, whatever.) I don’t even like true crime but this consumed me for half a day so I hope you enjoyed this ridiculously long footnote about it.

They note that this is one of Heinrich Kluver’s four form constants of hallucination: tunnels, spirals, honeycombs, and cobwebs

“Non-specific amplification of context” is a bit of a jab at the popular idea that psychedelics are magical substances that can change hearts and minds to bring ultimate peace and love for all — something Marcia Moore believed about ketamine, writing that it could be used for ‘the psychospiritual regeneration of planet Earth.’ But Brian A. Pace and Neşe Devenot have argued that psychedelics have no political agenda of their own — they amplify whatever politics you already hold, and history has plenty of examples of authoritarianism flourishing under psychedelic influence.

This study found that a good relationship with a therapist actually ‘predicts greater emotional breakthrough and “mystical type” experience’. So, you trip better with people you feel connected to (something I think those of us who have had psychedelic experiences outside of clinical settings already knew, but cool to see it reflected in research.)

detailed explanation starting at 12:15 in this interview

I would not particularly identify as a Tim Ferriss fan but this 3-hour interview with John Krystal is probably the most in-depth/accessible resource I found on ketamine psychiatry

You have probably heard a similar snow-based metaphor, where your brain is a hill and your thoughts are sleds carving paths down the hill, which can create ruts (depression, anxiety) that you get mentally stuck in, and psychedelics are like a fresh snow that provide a temporary clean slate for you to carve different paths. Micheal Pollen popularized this idea in How to Change Your Mind, but he got it from the researcher Mendel Kaelen.

which I wrote about a bit more here

Shayla Love wrote a great piece on this for Psyche

neuron image below comes from this project by the Queensland Brain Institute / Mississippi watershed image is from this video by NASA