Can Therapy Apps Make Your Neurons Grow?

On Brain-washed Advertising and Neoliberal Neurology

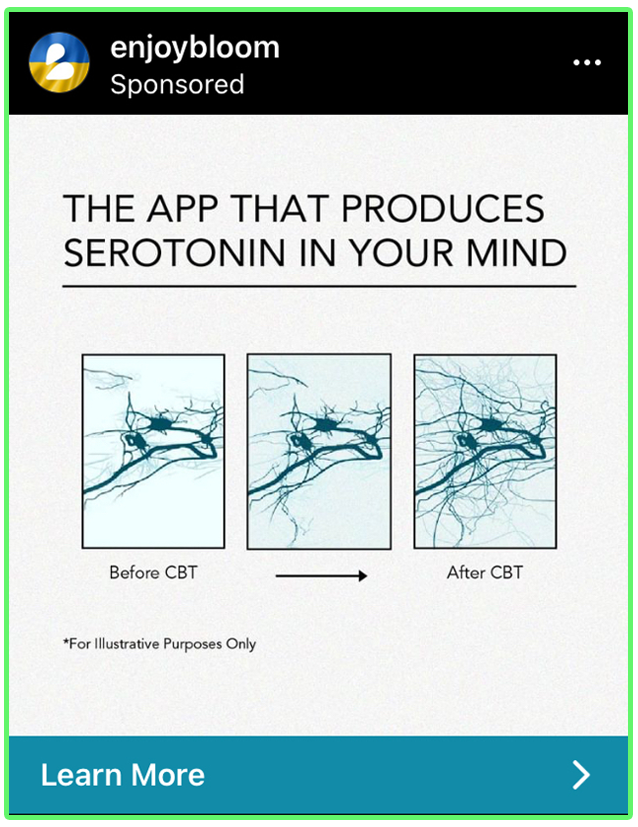

Have you seen this ad on Instagram?

It was posted in the SlugChat discord (thanks kiki!) and my eyes immediately zeroed in on the fine print: For Illustrative Purposes Only.

They put that there for legal reasons (and we will see why in a minute), but the ad implies that using this app will cause your neurons to grow. I immediately knew this was bullshit, but I didn’t do much digging until Ayesha sent me this screenshot the other day:

What is this, a template in Canva for Business? Maybe these companies use the same social media marketers, or one of them copied the other one, who knows, but the fact-checking area of my brain began to scream.

Bloom is an “interactive self-therapy app” based in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy created by Leon Mueller, an entrepreneur who majored in finance and investment banking and previously co-founded a “video micro-learning app for start-up skills”, according to his LinkedIn.

He told the Wellness for Makers podcast that, in the course of developing that app for entrepreneurs, they noticed more interest from users on topics like stress management and self-improvement, so they started researching self-administered CBT:

[We] realized how efficient and effective it is and how simple at the same time, and thought, how can we turn this into a product?

FitMind is a meditation app created by Liam McClintock, a Yale grad and former finance bro who travelled Asia to study meditation and decided to “re-brand” it for profit. He now calls it things like “mental fitness” and “self-directed neuroplasticity”.

Both of these apps claim to be “science-based” and “scientifically proven”, but is there any truth to it?

I mean, sort of. A little bit? There have been studies that show CBT and meditation change the brain, but as far as these ads are concerned, I couldn’t find anything specifically proving that they grow your neurons.

A 2018 review in Brain Sciences looked at studies that assessed neurobiological changes after CBT with imaging and found that none were placebo-controlled and only one was randomized, which they said “makes it difficult to draw formal conclusion whether the observed effects are CBT mediated or due to spontaneous recovery.”

All those studies looked at either blood flow using fMRI, PET, or SPECT scans, or changes to certain biochemicals like GABA, and inferred that structural brain changes happened based on before-and-after differences in brain activity.

There’s no technology that can take images of neuronal growth in living humans. Researchers are still working on mapping the mouse brain, and think it could be done sometime in the next decade.

Nature explains what imaging our brains would entail like this:

The human brain has 1015 connections and contains roughly the same number of neurons as there are stars in the Milky Way, around 100 billion. Using current imaging technology, it would take dozens of microscopes, working around the clock, thousands of years just to collect the data required for such an endeavour.

These “scientific” ads truly are just illustrative — they are illustrating an idea, not a scientific fact, but I don’t think most consumers see it that way.

It’s common for digital mental health apps like Bloom and FitMind to “neurowash” their advertising like this, but studies have shown that few apps have the data to back up their claims.

A 2019 mini-review of 293 digital therapy apps only found 10 supported by research, with no long-term data beyond 3 months:

Overall, 3.41% of apps had research to justify their claims of effectiveness, with the majority of that research undertaken by those involved in the development of the app.

A 2021 paper called “Is There An App For That? Ethical Issues In the Digital Mental Health Response to COVID-19” caused quite the discourse amongst academics by arguing that apps lacking evidence should not receive funding and could actually worsen health disparities.

These ads are referencing two neuroscience concepts that have received a lot of hype: neuroplasticity and neurogenesis.

Neuroplasticity has to do with how the brain changes over time in response to experiences — people often use the word “rewire”, although that is a metaphor. There is quite a bit of evidence for neuroplasticity, but neurogenesis, the theory that the adult brain can create new neurons, is still being debated.

Actually, the majority of evidence we have for neurogenesis comes from mouse studies. It’s only possible to study human neurogenesis in postmortem samples, and there’s all kinds of complications in that. It takes highly specialized training to get accurate results, and the simple problem remains that you can’t ask a dead person about their life experiences, so a lot remains unknown in these kinds of studies.

Despite the messy scientific reality, these ideas have become extremely popular in our media and are shaping the way we think about ourselves. Cognitive scientist and philosopher Mirko Farina writes:

“…the study of neural plasticity has also inspired a plethora of popular science books that have transformed the notion of neural plasticity into a panacea to solve all sort of difficulties and problems that humans can encounter throughout their lives.”

Neuroplasticity is all the rage because it provides neurological credence to capitalist ideas about personal responsibility and endless growth potential. I found a great paper about this by Victoria Pitts-Taylor called The Plastic Brain: Neoliberalism and the Neuronal Self, where she points out that our media likes to refer to the brain as a “resource”:

In popular accounts of the brain’s value as a bioresource, we are continually instructed that most people’s brains are underutilized. Again and again, the brain’s potential is presented as untapped.

..this view presents a competitive field where anyone can vie for brain prowess. Such logic also implies that those who do not have it might ultimately have to blame themselves.

Enter: the brain training industry, which uses similar language to the fitness world. I mean, it’s not even subtle — the app is called FitMind. In a blog post on their website, about the aforementioned “self-directed neuroplasticity”, they say:

“…thinking positive thoughts has been shown to produce epigenetic changes in the brain.”

The post references the pop science book The Telomere Effect co-written by Nobel Prize winner Elizabeth Blackburn, who co-discovered that nucleoprotein complexes called telomeres protect our chromosomes and get shorter with age.

A review in Chemistry World concludes that the book is just your standard nutrition/exercise/sleep hygiene advice wrapped in a scientific package, but it’s part of the hype these apps are building their houses on. You can change your own brain, if you just take responsibility for your health.

Thinking positive thoughts is the gospel of mindset influencers and hustle culture entrepreneurs everywhere.

Look at Mel Robbins, lawyer turned famous motivational speaker whose biggest teaching for overcoming anxiety is essentially just counting to five and thinking a happy thought instead. Or Gary Vee, heir to his dad’s wine company and lucky investor in the early internet, who tells people the key to success in life is optimism.

Over and over, people who are already rich and successful tell us that it’s only our “limiting beliefs” holding us back, that we can “manifest” anything if we just think positively enough, and the concept of neuroplasticity slots perfectly into this individualistic worldview.

Pitts-Taylor references philosopher Catherine Malabou’s work, saying:

Malabou finds global capitalism saturated with neuroscience-based language, so that neuroscience serves ideologically to naturalize global capitalism….I find the converse is also true: neuroscientific language about the brain, particularly that meant for laypersons, is saturated with neoliberal capitalist models of thought.

Fears about aging, slowing down, and falling behind are huge business opportunities in a society where your worth is based in your productivity, but your personal healthcare is “a responsibility or a duty rather than a right”, as Pitts-Taylor says.

In 2016, the Federal Trade Commission fined Lumos Labs, makers of the brain training app Lumosity, $2 million dollars for misleading advertising:

“Lumosity preyed on consumers’ fears about age-related cognitive decline, suggesting their games could stave off memory loss, dementia, and even Alzheimer’s disease,” said Jessica Rich, Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection. “But Lumosity simply did not have the science to back up its ads.”

According to the FTC’s complaint, the Lumosity program consists of 40 games purportedly designed to target and train specific areas of the brain. The company advertised that training on these games for 10 to 15 minutes three or four times a week could help users achieve their “full potential in every aspect of life.”

Of course, Bloom and FitMind cover their asses with that “Illustrative Purposes Only” fine print. I’m sure they could never argue in court that their apps can make your neurons grow like their ads imply, but marketers don’t need their claim to be real, they just need you to believe it.

idk why but the entire *for illustrative purposes only* thing is so funny to me, it's just a perfect metaphor for the whole industry. one could argue the chemical imbalance myth, too, was "for illustrated purposes only" 😆

Yes to all of this!!!